The Film: Onibaba (1964)

The Principals: Nobuko Otowa, Jitsuko Yoshimura, Kei Sato. Written & Directed by Kaneto Shindo.

The Premise: Our setting is medieval Japan, where a civil war has called off all able-bodied men and left the country in extreme poverty. A woman (Otowa) and her daughter-in-law (Yoshimura), who live in a tiny hut nestled amongst the towering, impenetrable grass of a riverland, eek out an existence murdering wounded samurai who get lost in the grassy chaos. They strip the samurais of their armor and weapons (to sell for food) and dump the corpses into a deep pit. It’s a lousy life, but it’s a living, as they say. But the women’s routine is interrupted by the return of one of their neighbors, Hachi (Sato). Hachi has deserted the army, and explains that the woman’s son – and girl’s husband – died in battle. Hachi quickly sets his sights on the girl. When the girl begins returning the sexual interest, tension rises between the three – for the woman does not approve. When a lost samurai, wearing a frightening demonic mask, crosses paths with the woman, things take a dramatic turn.

Is It Good: It’s a masterpiece. Onibaba (which literally means “demon woman”) is part character drama, part thriller, part horror movie, and part parable; almost like a medieval Japanese Tales From the Crypt story. The unusual nature of this mix is part of what makes it so interesting. The film is saturated with rich mythic symbolism, and while the exact meaning behind a lot of this symbolism may not fully come through to Western hemisphere denizens like us, nonetheless the texture of the allegories at work is like the film’s tall swamp grass — engrossing and inescapable. I can’t tell you exactly what the pit in the film represents, but it doesn’t matter. Just staring at it you know it is more than simply the place the woman and girl dump corpses. Its abyss-like blackness conjures up primeval feelings. And when the woman needs to descend into that blackness to retrieve something from one of her victims, you sense that she is plunging into more than just a sinkhole. She is – symbolically – entering a spirit world or underworld; a place she should not go. When she comes out, she won’t be the same, one could say. But as with any great work of symbolism, the film can also function entirely without it. It can just be a pit. It doesn’t matter, because in the end it is all about the characters.

The girl is mostly a pawn of the plot — there to cause conflict and be topless for a surprisingly constant amount of time for a 1964 film. The meaty roles are that of the woman and Hachi. Hachi is a pragmatist, so much so that you could also just call him a coward. He said “fuck this” to the war and came home. His real dishonor is how not dishonorable he finds his retreat. He wants the girl, which at first seems despicable to us, but the girl’s husband is dead. Maybe he’s not very tactful trying to get her so soon, but we come to realize how inevitable their coupling is. It’s just the three of them in this grassy swamp, after all. Following this same arc, at first the woman’s actions seem sympathetic. She seems to resent Hachi for returning while her son was killed, so fuck this guy thinking he can swoop in and take her son’s widow. But as the film progresses we soon sense that jealousy and petty fears are her true motivations in trying to keep Hachi and the girl apart. This comes to a head in the film’s best dialogue scene, in which the woman confronts Hachi, both telling him to stay away from the girl and also throwing herself sexually at him. Hachi’s demeanor is so rational in the scene, and the woman so frenzied and pathetic, that our opinions suddenly shift. Hachi may be kind of a fuckstick, but he’s just a guy. The woman is the sinister one. It is a great fucking scene.

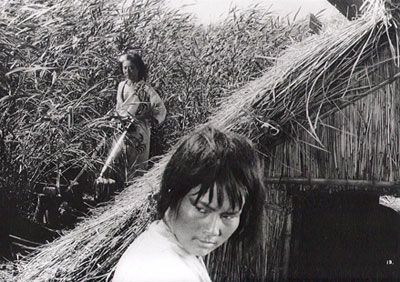

Kaneto Shindo does some phenomenal work here. I loved that he staged the samurai fights in a realistically unglamorous fashion, with grown men essentially swatting at each other with swords. But his stamp comes through most strongly with how he treats the otherworldly susuki grass. As a location, the giant grass destroys any ability for vistas and visual scope. Shindo has created an incredibly claustrophobic world. The grass in really our fourth central character; the film is filled with shots of the grass swaying in the hot summer wind, which while serene has the greater effect of making everything seem ghostly. Our characters seem to live in a bizarre fantasy-scape, which only heightens the film’s tone of a mythic ghoststory. It is almost as if the grassy swamp were limbo or some manner of purgatory.

Is It Worth Seeing: For a 1964 Japanese period film about a war you probably know nothing about (I certainly don’t), Onibaba is extremely accessible. It is exciting and surprising, thanks to the horror elements, and gorgeously shot (rendered lovingly in a Criterion release). Plus, hey, lots of nudity. I wouldn’t say that’s a selling point, but let’s be honest here — it doesn’t hurt. So I think it can appeal to a broader range of people than just those who enjoy vintage Asian cinema.

Random Anecdote: The look of the demon mask, which plays a pivotal role in the film, supposedly inspired the look William Friedkin gave the subliminal white-faced demon in The Exorcist.