There are endless cliches out there about the importance of a first impression, but whatever truth they may hold in our everyday lives they go double for film. When there’s only a couple of hours to tell a story and capture its players, an audience’s first chance to meet a character is an asset no filmmaker worth their salt is going to waste. So with that in mind, CHUD is going to take a look through the many decades of cinema to extract the most special of those moments when you are first introduced to a character, be they small moments that speak volumes, or large moments that simply can’t be ignored.

Inevitably it will be the major characters and leads that are granted the grandest of entrances, but don’t be surprised to see a few supporting players and minor individuals get their due, when the impact of their appearance lingers longer than their screentime. Also know that these moments may be chosen for any number of reasons, and the list could never be exhaustive. But here you’ll find moments that make a big splash, say a lot with a little, or we think are just particularly cool.

We hope you enjoy, and can’t wait to hear from you about each and every entry. Don’t spend the effort guessing future choices or declaring what must be included– just enjoy the ride!

—————-

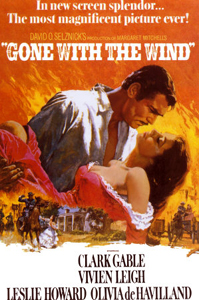

The Film… Gone with the Wind (1939)

Director… Victor Fleming

Entering From Stage Left… Vivien Leigh in the role of Scarlett O’Hara

What Makes It Special …The actress, the costume, and the sheer Southern fantasy of it all.

Over the years, a lot of the marketing mystique has been stripped away, and it turned out Vivien Leigh had nabbed the role a lot sooner than MGM legend would have us believe. She had been in consideration since February 1938, and in negotiations for months. But the idea that she just happened on the set as they were filming the burning of Atlanta was more fun for the newsreels.

In retrospect, it could never have belonged to anyone else. Leigh is Scarlett. You read the book, you see her. She was the perfect physical match (all right, so her eyes aren’t reallygreen, but that was nothing a bit of make-up, lighting, tinting and wardrobe couldn’t fix) and she nailed Scarlett’s maddening and intoxicating mix of stupidity, steel, and bitchiness better than any other actress could have. It’s rare that an actor or actress takes a beloved character of book or stage and runs away with it, making it inseparable from their own face and voice, but Leigh did. You still hear the odd person saying she was all wrong for Scarlett O’Hara. Those people are stupid.

But I’m getting ahead of myself! Let’s focus on the intro, shall we? It’s a quick and breathy one, just like the heroine herself. We zoom in on an impossibly grand plantation, through a stand of blooming magnolias (of course!) and onto the blue-coated backs of two red-haired boys. They’re talking to Scarlett, but we don’t get to see her until the last possible second. It’s the last wink of David O. Selznick’s marketing madness. Are you going to be disappointed in her? Of course not.

There she is, the epitome of a Southern belle. The scene is just dripping with “when chivalry took its last bow” stuff of the title card. It’s all dappled sunlight, courtly love, sweet magnolias, fabulous gowns, mint juleps, and happy slaves. War — the war — is the stuff of childish conversation. Scarlett’s suitors are eager to talk about it, dying for it to happen, and Scarlett is utterly bored by it. It’s a shadow on the happy scene, but only to us, because they’re wrapped up in their cocoon of wealthy, shaded bliss. What shatters their reverie isn’t the sound of cannon, but Scarlett going into a sulk at the news of Ashley Wilkes — her dream man, the one who will rule and ruin her life and so many others — getting married.

Oh, fiddle dee dee. Life is so hard.

Why It Resonates … It’s the iconography of it all. Gone with the Wind is a film that represents a number of things. It’s probably the epitome of the old Hollywood epic, released in the year generally assumed to be the very, very best of moviemaking. Its lushness is a stark contrast to the war raging across Europe, and the Depression eating at the hearts and souls of your average American. In truth, it’s more about the Depression than it is about the Civil War. Gone with the Wind is about “the good old days” of luxury and class, a fabricated notion of how wonderful life was before the government started bossing us around and trying to take what was rightfully ours. When you consider that Jim Crow was still raging — and possibly at its very worst — in numerous places, you can just see what a heady fantasy this taps into. Wouldn’t it be great if we could just go back to when they were happy working for us, and we were happy to take care of them in return?

But that’s getting into some sad and ugly territory, though it’s impossible to talk about Gone with the Windwithout touching it. You just can’t have Scarlett O’Hara sitting on the porch, playing with her magnolia blossoms, and not know what makes it all possible. It’s why it’s so alluring. She’s a princess, waited on hand and foot, with nothing pressing to do but look pretty and find herself a nice boy to marry. The slaves even mix the juleps so she won’t break a sweat in the process of courtship.

Other Grand Entrances … Is there ever! Just about every character in this film swishes into frame in a defining way (ineffective Ashley, retiring Melanie, her red-faced, horse-galloping father, the slimy overseer, Mammy) but only one character has an entrance that rivals Scarlett’s.

Who is that smiling rogue at the bottom of the stairs? He immediately catches Scarlett’s eye, which is no small feat considering Ashley is mincing about.

Ohhhh yeah. It’s Clark Gable as Rhett Butler, who has seen the girl he wants to take home. Twelve Oaks is packed with Southern belles, but he instantly sizes Scarlett up, recognizing she’s the only one who has any fire and backbone to her. It’s a casual entrance despite its dizzying zoom in, but it oozes testosterone, charisma, and power.

Scarlett actually blanches before him. “Who is that … he looks like he knows what I look like without my chemise!” As you know, that’s the 19th century way of saying “He just undressed me with his eyes! He’s totally checking me out!” And he is. Fittingly, they’ll part on a stairway with a similarly crude exchange. In a story that’s all about moonlight, magnolia, and chivalry making its last bow, Scarlett and Rhett had no time or patience for delicacy, good taste, or restraint.

![]()

Day 3: Groucho Marx (Duck Soup)

Day 4: Jackie Gleason (The Hustler)

Day 5: Orson Welles (The Third Man)

Day 6: Clint Eastwood (A Fistful of Dollars)

Day 8: George C. Scott (Patton)

Day 9: Grace Kelly (Rear Window)