“Deadwood” and “Deep Water” (Deadwood S1, eps. 1 & 2)

“The first human who hurled an insult instead of a stone was the founder of civilization.”

– Sigmund Freud

“And here’s my counteroffer to your counteroffer: Go fuck yourself!”

Al Swearengen

Here on Lost & Found, the mission is to resurrect and reappraise cancelled television shows. Some of them, like our last entry Carnivale, haven’t received much in the way of serious critical analysis. This makes it easier for an amateur like me to jump in and ramble on at length about the show without covering well-trod territory. Deadwood, on the other hand, does not lack for critical analysis. You can’t throw a virtual rock on the internet without it smashing into a half-dozen articles on this show. It’s going to be an interesting challenge to try and bring some new insight to the table, but it’s a challenge I’m happy to take up. If you’re looking for a recap of events you can hit Wikipedia. That’s not what I do here. It’s my intention to talk about some of the larger themes, history, and interesting bric-a-brac associated with this show. Because this show is sprawling and immense, it may take me a week or two to get my sea-legs, so to speak. Please bear with me as I do so. There’s a lot of ground to cover here, and because I’m not physically capable of writing a 30 page column I’m going to be breaking some of this stuff up over the first few weeks. Yes, Ian McShane is beyond awesome in this. We’ll get to him soon, along with a host of other topics. So without further ado, let’s get bric-a-brac-in’

The first two episodes of Deadwood tell a more-or-less complete story, making them a nicely self-contained introduction to the show as a whole. Taken alone and by themselves, Deadwood and Deep Water could function comfortably as a standalone TV movie.

What I’d like to focus on here at the start of my coverage is the overall elegance on display, along with one or two of the major themes at work. Think of it as an extended introduction to the show, and a chance for me to stretch new writing muscles as I figure out how to effectively cover this behemoth. In Deadwood’s first two hours the show does some serious heavy-lifting – introducing over a dozen major characters, several key locations, some important thematic elements, and a fistful of plotlines that will play out not only across this first season, but beyond. But is it right to call it heavy-lifting if all that effort seems, well, effortless? Because that’s the word I’d use to describe the feel of these two episodes: effortless.

Bullock, Starr, Swearengen, the Garrets, Dan, Doc, Jane, Bill, Charlie and Trixie (to name the majority of the “featured players” at this point) all have separate storylines and vivid lives etched out here, all of them happening at once. While some characters receive more shading than others (Trixie’s pretty darn similar to one of the vengeful prostitutes of Unforgiven, Alma’s essentially Wyatt Earp’s doped-up wife in Tombstone), all of them receive enough color and definition to make clear to us that this show plans to explore these characters lives in intimate and surprising ways. By the time Deep Water ends we have a fantastically-clear sense of who all these characters are, as people, at this point in their stories. If you’re like me, you think most of them are already inherently interesting. And all this is accomplished without filling half the episode with medical/technical/procedural jargon, or mawkish, unearned sentiment.

These first two installments also lay out a fully-realized, deeply-textured world for us to get lost in. Deadwood’s sets and locations are extraordinary; practically-achieved, without the layer of unreality that CGI provides. The camp itself is a marvel of production design – every square inch of Deadwood has been thought through meticulously. This is an area in which HBO has never been bested. They spend impressive amounts of money to create believable, lived-in worlds, whether that’s the America of the Great Depression or the Dakota Territory of 1876. They built an entire town, fer chrissakes. Beat that, NBC.

CGI is for cocksuckers

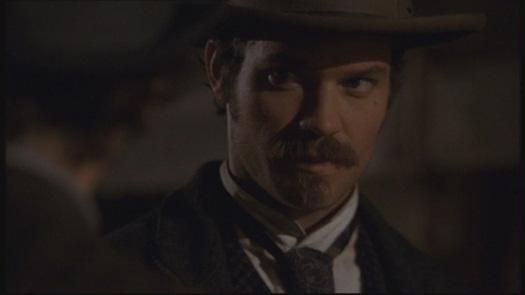

This attention to detail suffuses the show. Costumes and props are all era-appropriate, and the characters themselves are largely drawn from historical record. The people who populate this fiction existed. Al Swearengen really did run The Gem Saloon. Sol Star really did open a hardware store with Seth Bullock. Wild Bill Hickok did come to town with Charlie Utter. A prostitute named Trixie actually shot a man in the head, only to watch the man live on afterward for an unusually long time.

Deadwood goes about telling its story by hanging it on the bones of historical fact. But despite those bones it’s still a story, still a fiction. It takes liberties where it feels like taking liberties, as in its dialogue which – as I noted in the intro column – may be historically ‘inaccurate’** Some events here will closely parallel the historical record, some will stray far afield into complete fiction. It doesn’t matter. Milch is using history to craft myth – using actual people to create what amounts to a massively intricate meditation on law, order, community and change.

Clell Watson: “No law at all in Deadwood? Is that true?”

That’s not true, actually. There’s law in Deadwood from the start. It’s just that it’s Al’s law, not Deadwood’s law (though those two things are more-or-less synonymous in the beginning). Over and again we watch as Al holds court, presides over “one fucking thing after the other.” And this makes sense. Al has power in this camp. To maintain that power he needs to maintain control and a semblance of order insofar as it gets him what he wants. Neither law nor order are Good or Bad, right or wrong. They are instead receptacles for the will of those who establish them. And in Al’s case, his version of law involves maintaining his desired sense of order and control.

“Our desire for order comes first, and law comes afterward.” – David Milch

In Deadwood, “order” is literally embodied in Al Swearengen, who arrived in the town first, and who has indeed established a rough but clear order in the camp.

Seth comes after. He’s a literal embodiment of the law. Milch underlines this point by having Bullock carry out the show’s opening scene/execution (and what a scene! What an execution!). It is an act of law for the sake of the law. Does it really “matter” whether Seth executes Clell Watson under color of law, or whether Byron Samson hangs him via lynch mob? Either way, Watson dies for the crime of horse theft. Either way, the wrong (the theft) is rectified by death. But Deadwood makes the statement here (and in the future) that it does matter. It matters because law is an agreement between men to maintain a semblance of civility. It matters because the distinction between hanging under color of law and hanging via lynch mob comes down to a societal agreement that order is necessary. To have a just order, you need just law.

Al’s discomfort with the idea of a former Marshall being in town isn’t so much about Bullock himself as it is about the idea of Bullock – what his arrival means in the larger sense, in that it signals a change in the order that Al has bloodily but effectively forged from his own two stab-happy hands. It signals a move toward a more inclusive and stable sort of “order,” via the imposition of overarching law. And once that happens, Al is no longer the one determining what “order” means in the Deadwood camp.

Seth Bullock: “You called the law in, Samson. You don’t get to call it off just because you’re liquored up and popular on payday.”

Byron Samson: “And you don’t get to tell us what to do and what not to do.”

Speaking very, very broadly, that argument – between “you don’t get to tell us what to do” and “this is what the community needs” – is one that will recur over and over again throughout Deadwood’s seasons.

Most folks will tell you that the story of Deadwood is the story of the evolution from savagery to civilization. I think this POV is sorta misleading. The creation of civilization doesn’t put savagery in our cultural rear-view mirror – the two concepts can and do proceed together hand-in-hand. In many cases, the advances of civilization enable a more monstrous form of savagery; what’s more savage and horrific: a man cutting another man’s throat in the wilderness over a personal vendetta, or a man remote-piloting a drone that can kill people he’s never met from thousands of miles away while seated in a comfortable leather chair?). Deadwood will repeatedly show us that “civilized” men are every bit as savage as their less-civilized brethren, and that “civilization” is often an excuse to behave abominably.

And yet, along with civilization comes Community – a place of belonging, in which people of varying dispositions and talents agree to live together for their collective benefit. Community is no guarantee of equality, nor any guarantee of survival. Some of these characters would prefer to do without it entirely. But in a world that sees wolves both literal and figurative stalking the hills and saloons of Deadwood, the concept of Community is one of the few things these people have to count on. Law and order are necessary to maintain the harmony and balance of any Community.

Along with all these highfalutin’ themes and whatnot, Deadwood’s introductory episodes also focus in close on three fascinating men – men who act as reflections of each other in some incredibly interesting ways.

In a sense, the first two episodes paint a portrait of three very different men that are, on real level, very much the same man. Al, Bill and Seth are all more or less defined by the boundless well of anger they all draw from. How they’ve channeled their personal violence has led them all to this place. Bullock takes an instant, instinctual dislike to Swearengen. I like to think that it’s because he recognizes something of himself in Al – the same coiled, ready violence.

The similarities between Bill and Seth are also pointed up here. As Charlie notes, Bill and Seth are alike, but Seth has something that Bill’s missing – something that keeps him from his worst impulses (sometimes). That something is arguably Seth’s near-pathological hatred of injustice/need for justice. He pointedly leaves his badge behind in Montana, but he’s soon leading a posse of men to investigate a murder. Bullock seems almost desperate in the way he clings to Law and an honorable code. It’s as though he realizes that this is pretty much the only thing keeping him from becoming Bill or Al.

And yet, it’s not a simple substitution either. These are still different men, with different motivations and different goals. Seth Bullock seems physically repulsed by Al Swearengen in a way that signifies how alike they are in violence, but also how different they are in the way they channel that violence.

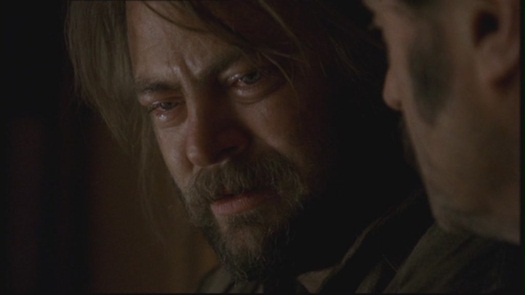

And violence is key to Deadwood. The show plays rough. By the time Dan appears on Doc’s door to kill a child, there’s been enough bloodshed to make us believe that he’ll go through with this sickness. He’s crying, but he’s there, and his hand’s steady enough. Dan makes it clear that he doesn’t want to do this, but that he will do it, because Al’s displeasure is worse than the soul-destroying act of murdering a child (contemplate THAT for a second). The girl survives because Doc convinces him to reconsider, and that’s where I think the heart of this show lies.

Milch intends to show us every darkness here, from whoring to depression to addiction to murder and on and on and on, but there’s a fierce, cynical humanism at work here as well. Reverend Smith may look/be a little crazy.

Okay...a lot crazy.

But he’s also a man that Seth and Sol entrust with their livelihood, and that trust is well-placed. He is, behind those CRAZY EYES, a good man.

Doc Cochran may come off like Frankenstein’s assistant in his first scene, but he’s revealed to have a doggedly-stubborn decency that’s as fierce as Seth’s temper. Drunken, ultraprofane Jane becomes an alternately hilarious and touching mama bear toward the young “squarehead” that’s rescued. Charlie spends the entirety of his screen time hovering, nanny-like, over his friend Bill, hoping to halt Hickok’s weary slide into self-destruction.

Life may be a raw, cruel thing for these people, but some of them are willing to work at being better than their worst impulses, and it’s from that communal desire to live an orderly, less savage life that true Community will arise.

Stray bullets:

- Each week I’ll fit some random observations in here at the end. This is the stuff that I can’t find a way to work into the main body of the article. Writing about this show is going to require a new approach from me, and I’m hoping that “stray bullets” will help keep me on track while allowing me to do the digression thing I so love doing.

- Hey! Ron Swanson! Nick Offerman, who plays Uber-Man Swanson on Parks and Recreation, shows up here as a drunken, filthy degenerate and does a fine job of it. Now raise your hand if you never, ever want to see Nick Offerman naked again.

- Seth and Sol set out for Deadwood together. Next thing we know, Seth’s riding into town alone to meet up with Sol, who’s just located the lot for their hardware store. I imagine the explanation for this is that Sol went ahead on foot due to the wagon delays, but it’s still weird.

- Hey! It’s Garret Dillahunt as Jack McCall! Dillahunt is a terrifically-gifted character actor. He’s appeared in everything from The Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles to Raising Hope to Winter’s Bone to No Country For Old Men and seemingly every major police procedural, like, ever. This isn’t the only character that Dillahunt will play on Milch’s show. Keep your eye out for him in future seasons. It’s like Where’s Waldo, only without the striped shirt or the eerie incongruity of appearing amidst piles and piles of dead people.

- A word about swearing and Deadwood: I wasn’t kidding, was I? They’re going for some kind of World record for profanity on this show. You may find this pretty distracting at first. You’re supposed to. It’s distracting. But take a moment to process what’s really happening here with all the various fucks and cocksuckers being tossed about all willy nilly: Milch is crafting a form of speech that’s intended to remind us with every word that these people are rough and tumble. And the sheer volume of profanity here quickly immunizes most people to its impact, which I would argue is very much the point. After a few episodes the word “cocksucker” will feel as transgressive as, say, “poodle.”

**Sidenote: Nerds exist in every facet of our culture. A sci-fi nerd will ask Captain Jason Nesmith why the plans of a spaceship don’t match up with a description on a tv show. A History nerd will angrily insist that Deadwood’s dialogue is ‘wrong,’ despite the show having no intention of trying to portray “historical fact.” This is weirdly comforting to me. Many of us are obsessive geeks of one kind or another.

All screencaps courtesy of Magic Hours