“The Trial of Jack McCall” & “The Plague” (Deadwood S1, eps 5 & 6)

“I cannot exclude the possibility that God would save all men at the Judgment.” – Karl Barth

Charlie: “His way to heaven is above ground and facing west.”

Welcome back to Lost and Found, where we resurrect and reappraise the cancelled television shows of yesteryear. As of this week we’re halfway through Deadwood’s first season. If you missed last week’s column you can catch up right here. If you’d like to check out the other shows I’ve covered, you can surrender several days of your life over here. Want to spelunk around in my brain? Follow me on Twitter.

A good number of people smarter than I have already noted that the Deadwood camp more or less functions as a microcosm of civilization, and that on a metaphorical level the camp’s body politic can be said to represent the human body. Those same wicked smaht fellas have also noted that, in The Trial of Jack McCall and The Plague, Deadwood fully embraces the concept of camp-as-metaphor-for-Community-and/or-humanity-and/or-the-human-body; pointing toward Reverend Smith’s choice of Scripture for Wild Bill’s funeral in The Trial of Jack McCall as evidence of the show’s intention to make this analogy overt. Check it out for yourself:

Reverend Smith: “For the body is not one member but many. He tells us, the eye cannot say unto the hand, ‘I have no need of thee.’ Nor again the head to the feet, ‘I have no need of thee.’ Nay, much more those members of the body which seem to be more feeble, and those members of the body which we think of as less honorable, are all necessary. He says that there should be no schism in the body, but that the members should have the same care, one to another, and where the one member suffer, all the members suffer with it.”

In other words: Each member of a Community has a Purpose. Each member of a Community has a contribution to make. Each member, no matter how diseased, no matter how pathetic or hobbled, matters. More on this below.

But first, some nifty trivia: The historical St. Paul underwent a conversion experience on the road to Damascus which transformed him from a persecutor of Christians into a Christian himself. Some folks, David Milch included, now believe that Paul’s experience may have been the result of an epileptic seizure, so it’s fitting that Milch gives Smith the same seizures. It’s also interesting to note that this material – Bible quotes and theories regarding the value of Community – is essentially recycled from Milch’s original pitch to HBO: a show about Roman “cops” that would have explored concepts of “order” and “law” in ways similar to Deadwood, and which would have featured the Roman cops arresting St. Paul in the first episode.

Second, here’s a little something to chew on, thematically-speaking: If you’re feeling pretentious (and I am! I am!) you can draw a connection between the Smallpox which threatens the camp and Jack McCall’s murder of Wild Bill Hickok. In a very real sense, McCall functions as a personification of a virus. When you introduce a virus into the human body it throws the body out of whack (as McCall does to Deadwood’s “body”) and destroys living cells (McCall’s killing of Bill). In the metaphorical sense, McCall is a virus introduced into Deadwood’s bloodstream, and inoculation against further infection of the larger town-body is accomplished through a trial; through the application of Justice and reason to a despicable act. Jack McCall is the figurative harbinger of the literal virus that follows in his wake.

“The primary responsibility of the physician is not curative but pastoral.” – David Milch

Todd VanDerWerff of the AV Club (a terrific writer whose shoes I ain’t fit to shine) has written that he doesn’t believe Deadwood to be a particularly religious show, but I couldn’t disagree more completely with that perspective. Deadwood may not be “religious,” per se, but from where I sit on my couch Deadwood is profoundly spiritual (and I do not use the word “profound” lightly); it’s just that the sort of spirituality it offers up is anything but traditionally pious. It’s the spirituality of hardscrabble men and women attempting to grapple with mortality and morality in an environment where both concepts have an immediacy that’s palpable. It’s the sort of spirituality that arises not from theoretical suppositions, but from personal agony and ecstasy. It’s a spirituality that grows out of, and is arguably based in, the notion of Community and the mutual respect and genuine care that Community demands from individuals.

To wit: when Reverend Smith, afflicted by mysterious seizures, nonetheless volunteers to help in the Pest Tent and tend to the Smallpox sufferers he tells Doc Cochran that he is “right where he’s supposed to be,” and the purity of certainty that lights his face in that moment is simply breathtaking – the spiritual made concrete and literal. It speaks of a devotion that transcends selfish impulses and achieves a kind of selfless divinity. In fact, I’d argue that while the above quote from Reverend Smith is undoubtedly a summation of Deadwood’s larger concerns, there’s another Smith quotation that’s almost as important to the show as a whole:

“I believe in God’s purpose, not knowing it. I ask Him, moving in me, to allow me to see His will. I ask Him, moving in others, to allow them to see it.”

And on that line, Smith pauses and stares directly into Seth’s smoldering eyes. This is no accident. Seth spends a good portion of The Trial of Jack McCall struggling against what others think his “purpose” should be:

Reverend Smith: “May I ask, Mr. Bullock, what you feel now may be your part? I would not impose, but it has been given to me to ask.”

And later:

Sol: “He looked pale to me.”

Seth: “What if he was? Let’s say he was. Will you shut up about it? ‘What is my part? And your part? What part of my part is your part? Is my foot your knee? What about your ear?’ What the fuck is that?”

Sol: “Yeah. I don’t know.”

Seth: “What don’t you know? If he was pale or not?”

Sol: “What you’re supposed to do.”

Seth: “I’m not supposed to do anything! Let’s agree to that. Not one fucking thing that I don’t decide I’m gonna.”

Ironically, it is now Bullock who finds himself arguing the same position that Byron Samson took in the first episode – essentially, that no one else gets to tell him what to do; and there’s a strong sense throughout these episodes that Bullock’s purpose is something already known to him that he cannot quite face; something he already carries inside of him, a compulsion he can’t shake – namely, his thirst to see Justice done. Whether or not God actually exists in Deadwood is beside the point – what God represents (unity, totality of devotion to your fellow man, sacrifice and Love) DOES exist, and has always existed so long as the notion of Community likewise exists.

“Hawthorne said that man’s accidents are God’s purposes. We miss the good we seek and do the good we little sought. Why Swearengen thinks he does it and why God wants him to do it might be totally different things.” – David Milch

The above quote is taken from an interview with Milch that you shouldn’t read unless you’re comfortable with being spoiled. It refers to Swearengen, but in the larger sense it could apply to any of Deadwood’s characters – especially Bullock, whose desired “purpose” seems at direct odds with the purpose God intends for him.

But Bullock’s purpose (tracking McCall and exacting justice) and God’s purpose (waylaying Bullock so that he might meet up with Charlie Utter and decide to honor the dead instead of pursuing the living) are not the same. Note that Seth’s story arc in this episode involves him setting aside his burning desire for vengeance in order to honor the burial beliefs of the Sioux tribesman that tried to murder him. Charlie’s comment to Seth about how the Sioux prefer to be honored after death tells us all we need to know about the kind of respect required to survive in a true Community – the kind that needs each of us to accommodate our fellow man and set aside our anger in order to achieve order and a kind of grace. When Jane describes Wild Bill in these episodes, she describes him as the kind of man who “took you as he found ya, thought the best of ya.” The same could be said of Reverend Smith’s tearless God, watching over the wicked and the innocent alike. The same could be said of Deadwood itself – a community that will take each person as it finds them.

But that quality of acceptance (leavened as it is with a serious helping of “watch yer fuckin’ step, lest you end up in some celestial’s pig sty) isn’t some hippie-dippie creed. It comes furnished with responsibilities which, unattended to, will leave you in some serious fuckin’ shit.

Case in point: note that the Smallpox outbreak arguably begins to spread because Cy Tolliver does not care for his fellow man. He has Andy cast out of camp and leaves him in the woods to die. As the show progresses, it’s becoming clearer that while Al is clearly capable of being an absolute monster, he’s also capable of being a decent man. Cy, on the other hand, seems cold as winter, through-and-through. There’s warmth to his professional exterior, but there’s none at all once we peer past it to the man who inhabits that exterior. When Eddie gently admonishes Cy by saying “she liked Andy,” Cy responds, “I liked him too.” And yet there’s nothing behind his eyes in that moment but flint. This is a perfect example of how the advancement of “Civilization” in no way guarantees advances in humane behavior.

And so but anyway, Reverend Smith’s speech does not simply point to the idea of Deadwood as one “body.” It also functions as premonition and as a kind of divine warning: “He says that there should be no schism in the body, but that the members should have the same care, one to another, and where one member suffers, all the members suffer with it.”

Cy Tolliver did not heed this warning, did not have the care for Andy required of him according to Paul, and now all of Deadwood will suffer for it. Al Swearengen may be a monster, but he does recognize the truth of Reverend Smith’s words (and note how respectful Al is to Smith overall – there’s a near-tenderness to the way he handles Smith’s seizure in the Gem, and that includes his not-quite-brusque dismissal of the man). Al takes on the mantle of “Community leader” in both these episodes, and in both cases he does so in order to ensure that his interests are served. In the process, he ends up serving the camp’s best interests as well, and its here that we can see how the show is carefully going about illustrating how the observance of law and the maintaining of order necessarily dovetails with individual, selfish desires; how the work of stabilizing a community often begins with individuals ensuring that their own interests are looked after.

Al recognizes that he and the camp are as one body, and he reacts to the appearance of Smallpox with that same recognition. What harms the camp will harm him, and so he must act to protect the camp however he can. This same curious mixture of selfishness and selflessness also informs his manipulation of Jack McCall’s trial. A “guilty” verdict may bring with it the attention of the “big vipers” in Washington and give them cause to view Deadwood as a “sovereign nation.” By arranging to have McCall declared “innocent,” he keeps the camp off the radars of the U.S. Government a little while longer. While he does this to protect his own interests, the result of this is that Deadwood maintains its independence a little while longer.

E.W. Merrick: “What luck for me, Al, that you have such a keen editorial sense.”

The Plague also gives us some insight into the role of the Press, showing us how the town’s local newspaper is used to help allay fears about the possibility of a Smallpox outbreak. David Milch and his writers are powerfully-keen observers of human ritual, and they say a lot about the ways in which media is manipulated to serve individual interest without ever getting up on a soapbox to make their point. That the individual interests being served here are also arguably communal interests is very much the point.

These two episodes show us again and again the simple power of compassion to move us and to help us as people. Deadwood is almost shockingly hopeful in this sense. In times of real trial – an outbreak of what might poetically be called a Biblical plague (an association that the title of The Plague encourages) – this camp comes together to support one another. Trixie disobeys Al and helps Alma to fight her laudanum addiction. Joanie takes pity on kindly Ellsworth instead of fleecing him silly at the Craps tables. Al and Cy work together to set up a place where the afflicted may be treated.

That sense of compassion extends directly from the hand of the show’s Creator, and there’s a strong sense of specificity to the scenes of Alma kicking her laudanum habit. The fact that David Milch is an ex-junkie goes a long way toward explaining the matter-of-fact, often startlingly-sympathetic portrayals of the various-and-sundry addicts strewn about the camp. These episodes mark the second time that Doc Cochran tells Jane she “has a gift,” and Robin Weigert spends these two hours giving Jane a depth of emotion in her grief that suggests the source of that gift and the cause of her prodigious drinking all at once. Addicts often use to dull the intensity of their emotions, and Jane seems cut from that cloth. And while Milch extends to her the same lovingly-tearless grace that’s extended to all characters on the show, he’s never hesitant to show us how utterly freakin’ ridiculous an addict can be. That even-handedness makes a character like Jane poignant and hilarious in equal measure.

Magistrate Claggett: “This camp is part of no territory, state, or nation. You of the jury are therefore without the law upon which to decide this case. How then are you to decide? You must rely on common custom.”

There’s no real law in Deadwood, but for order to truly exist, and for Community to flourish, some kind of law needs to be obeyed; Deadwood seems to be setting forth the argument that the idea of “Law” isn’t entirely a social creation – that notions of Right and Wrong are embedded into each of us, giving us the ability and the prerogative to cast judgment when the Community requires. The men and women of Deadwood may be beholden to no established law, but they remain beholden to each other – and that primal, inescapable bond defines this series.

Stray Bullets:

E.W. Merrick: “Should it ever be our misfortune to kill a man…we would simply ask that our trial may take place in some of the mining camps of these hills.”

- Merrick’s words here are actually taken from the editorial page of the real Black Hills Pioneer. Incidentally, the Pioneer is still in existence. I think that’s awesome.

- I don’t know about you, but the scene between Jane and Andy in The Trial (“I apologize”) cracks me right up. This show tickles me like few others, because the humor comes so organically from such well-realized characters. Take a listen to Jane’s side of the “conversation” between them and note how her half of it evolves up to that perfectly timed “Shut the fuck up!.” I love the way that Robin Weigert plays Calamity Jane, slurring her speech so badly at times that she sounds like she’s gumming on a mouthful of marbles. It’s a brave and utterly vanity-free performance, and its indelible stuff.

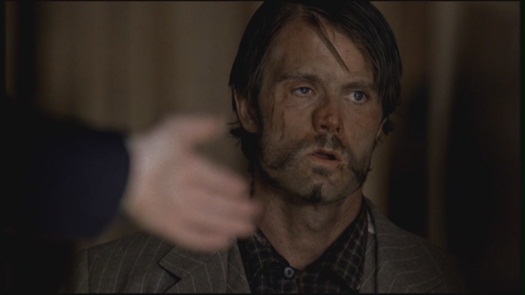

Macgruber! He got stuck in the Old West and now he’s dyin’ of some Smallpox yeah, Macgruber!

…Macgruber!

Seriously though – does that guy look like Will Forte or what?

- We’re told that the tribesman’s companion is headless, indicating that the attack on Seth occurred because of Al’s promise to pay $50 a head for Sioux scalps.

- The peaches and pears that Al has placed out for their meeting is a small signifier of civility and civilization, and its telling that this one small act initially flummoxes Al’s henchman, Johnny. Little grace notes like these not only function to illuminate character within the show – they also function to illustrate just how Deadwood the camp evolves into Deadwood the Community.

- Deadwood is often described as being “Shakespearean,” and The Trial of Jack McCall offers a perfect illustration of what people mean when they say that: E.B.’s monologue. Specifically, the monologue he gives while scrubbing the floor to try and remove the stain of Tim Driscoll’s blood. It’s worth reproducing in part here. Allow me to fiddle with the text arrangement a bit while I’m at it:

“You have been tested, Al Swearengen.

And your deepest purposes proved,

There’s gold on the woman’s claim.

You might as well have shouted it from the rooftops. That’s why

I’m jumping through hoops to get it back.

Thorough as I fleeced the fool she married,

I will fleece his widow, too

Using loyal associates like Eustace Bailey Farnum

As my go-betweens and dupes.

To explain why I want her bought out

I’ll make a pretext of my fear of the Pinkertons.

I’ll throw Farnum a token thief!

Why should I reward E.B. with some small fractional, participation

In the claim? Or let him even lay by a little security

And source of continuing income for his declining years?”

Shakespeare’s canon is disappointingly lacking in “motherfuckers” (his idea of cursing someone out? “I bite my thumb at you, sir!”) but there’s a weird kind of similarity in the flow and the tenor of the language, a flow that’s helped along nicely by the line readings that William Sanderson gives in the scene. The phrase “thorough as I fleeced the fool she married, I will fleece his widow too” sounds plucked from one of Bill S’s lesser-known works.

Fightin’ Words:

Farnum: “Be brief!”

Jane: “Be fucked!”