I can’t imagine sitting down with Courtney Solomon and not asking him about his last film, Dungeons & Dragons. It can be weird asking someone about their shitty previous work – sometimes they seem to deny that the film was no good; other times they just say that the movie made a bundle in pay TV sales. It’s pretty rare that they actually spill some of the behind the scenes details that went into making the movie a mess, and even rarer when they say that Gary Gygax was on a coke binge. You go, Courtney.

I can’t imagine sitting down with Courtney Solomon and not asking him about his last film, Dungeons & Dragons. It can be weird asking someone about their shitty previous work – sometimes they seem to deny that the film was no good; other times they just say that the movie made a bundle in pay TV sales. It’s pretty rare that they actually spill some of the behind the scenes details that went into making the movie a mess, and even rarer when they say that Gary Gygax was on a coke binge. You go, Courtney.

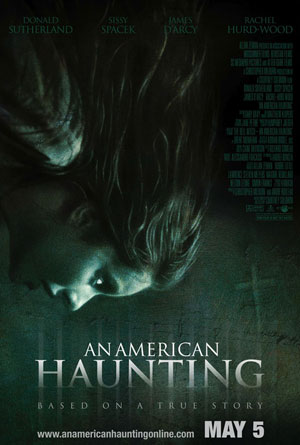

Solomon has clawed his way out from beneath that wreckage to make an effective little horror film, An American Haunting. It’s based on the fascinating, and ostensibly true, Bell With case from Tennessee in the 1880s. Solomon’s film is filled with great actors, especially Donald Sutherland and Sissy Spacek as the parents of the girl who is tormented by the mysterious poltergeist.

An American Haunting is marked by the fact that it’s already been released in the UK in a radically different cut. I’ve seen both and find it interesting that Solomon recut the film for American audiences, and that his cast all seem to think it’s made the film better. I made sure to ask about that, too.

But first – Dungeons & Dragons.

Q: Were you a little burned out from your project before this? Is that why it’s so long between films?

Solomon: No. Well, I had to recover, right? I didn’t like my project before this. So, you know, I’ll be honest about it. No, I mean, it wasn’t very good so it wasn’t quite so easy to get your next project done. And Hollywood’s not a very forgiving town, is it? You do a crappy movie and they’re not too interested. You do a good movie and you know you have seven offers that you don’t have time to read.

Q: Unless the crappy movie makes money.

Solomon: The crappy movie made money. I mean we made a sequel; Joel [Silver] and I did a sequel. I mean we made good money – hey, I don’t look like a schluff. You’re not making films to make money – go to Wall Street make money. Films you should be doing some sort of passion, I mean that’s you know, why you get into the business. I mean that’s just my viewpoint, maybe not everybody. But no, it was just hard to get it done.

I actually started this project before I actually did Dungeons. I was working on for a long time, but I found the actual book and started working on it. Then I did DungeonsDungeons and then I went back to it after I took about six or nine months off and then came back to this movie.

Q: How did that sort of affect the way you approached this? You didn’t like the way Dungeons and Dragons turned out. Now you’re coming out with your next film, how do you make sure that you do like this one?

Solomon: I wrote this one. So that made it a lot easier for me. I mean Dungeons had a lot of stories. I know I don’t really talk about it all that much but it has a lot of stories behind it because I got those rights when I was like nineteen or twenty and that company changed ownership many times. And when I originally got them, being so young with no track record, I gave them director approval on the rights agreement, I gave them script approval on the rights agreement. Things a studio would never, ever give.

Q: The company at that time was –

Solomon: TSR. And the woman that owned it was like a trust fund baby and she got this company for like, I believe you know, a couple hundred grand from Gary Gygax because he spent it on some coke binge or something – as the story goes. I can’t validate if that would  be true or not. But that’s how the story goes. So she picked it up, and when I went in to her and I came up with this whole thing, when we did the script for example, she was like, ‘I want to make toys.’ I’m like, ‘Lady, your audience doesn’t want to buy toys. That’s not who the D&D audience is. You gotta make a different film.’ She didn’t care.

be true or not. But that’s how the story goes. So she picked it up, and when I went in to her and I came up with this whole thing, when we did the script for example, she was like, ‘I want to make toys.’ I’m like, ‘Lady, your audience doesn’t want to buy toys. That’s not who the D&D audience is. You gotta make a different film.’ She didn’t care.

And what happened was, you know, long story short, you know. I got, you know, Jim Cameron to agree to do it at one point in 93. She sits at the Bel Air Hotel Restaurant [with Cameron], she folds her arms, she looks at him and says – its 93 – she says, ‘What are your qualifications to direct this film?’ I was like, ‘OK, Jim, please don’t kill me right now. I know about your temper, please don’t do it. Ok.’

Look, at twenty-three as a producer, I originally only intended to produce Dungeons and Dragons. That was the thing, I could get the rights, go to Hollywood, get a big director like Jim Cameron, hey I brought her Francis Coppola, I brought her Renny Harlin in the early 90’s. At that point these people were hot, and she turned them all down, she had the approval.

So then she lost her company – what a surprise – about three years later and Wizards of the Coast bought it. The guy who ran Wizards of the Coast stepped into it like a lucky shit, you know, he’d gotten Magic: The Gathering, made a ton of money really quickly, bought the Dungeons and Dragons company and at that point I had gotten involved with Joel Silver. We had rewritten the script to be a good script that should be D&D, we were attaching a filmmaker and we had it financed for a decent amount of money. And that guy came in and he started a lawsuit with us just as we were about to shoot. So financing, everything all falls through, we have to fight with these guys. We settle with them because their lawsuit was bogus and we’d been working on it for six years. But part of the settlement was we had to go within a certain amount of months and start production on the movie or we’d lose our rights entirely, that was just the easy way out because who gets into this to fight a lawsuit.

At that point my investors had put a lot of money in, they said, ‘You know this movie better than anybody. You’re directing.’ I’m like, ‘I don’t want to direct this movie.’ And then, part of the settlement was, I got stuck having to do the script that she originally approved many years earlier. And they did it on purpose because they wanted the whole thing to fail. I was like, ‘You guys are fools. It’s your property, why do you want to do this?’ They didn’t care. The guy just had blinders on. So, whatever, we had millions in, time in, everything else, we had obligations to people so that’s it. That’s not how you want to direct your first film. My original plan was, I’m going to produce this, start to make a name in Hollywood, learn from a big director and then go to direct my first movie.

OK, all said and done, and there were a lot of problems afterwards, all said and done, great learning experience. What did I bring back to it? American Haunting. Looking at it, I know what I did wrong personally. I knew what I wasn’t in control of personally Dungeons and Dragons. So I tried to learn as much as I possibly could.

Q: What did you learn?

Solomon: Oh, so many things. From working with actors to scripts to how to shoot your film, to the type of crew you need around you. And the biggest lesson you learn is you need great people around you to support you that are great too. You want Adrian Biddle as your DP. I mean rest his soul, you want Adrian Biddle as your DP and his entire crew. I used a local Czech crew before they were doing a lot of movies there, when I did Dungeons. So it wasn’t that I wasn’t coming up with exciting shots, I was at least doing that. They couldn’t actually execute the exciting shots. If you don’t have the grip department that can do it, what you end up having to fall back on is, All right, leave the camera there, shoot, get it in the can, get your coverage. That’s a simple example for you. But it goes all the way to production; it goes to every department. So you really have to surround yourself with good people and also, you don’t want people to do a movie – because it happens a lot – just because they’re getting paid. Happens all the time. Those are usually the ones that don’t turn out so well. I won’t mention any names, you know, but I mean certain people got paid on Dungeons and Dragons. You can figure it out; you’re bright.

That’s why when Donald and Sissy got involved in this project, I mean, legitimately they wanted to do it. It wasn’t about the money because we didn’t have a lot of money. I mean they got paid decently but they didn’t get overpaid or just do it for that reason, and they’re not the type actors that do that because they don’t need to. And that makes a huge difference because it makes a difference in they work on the script with you. When they’re on the set with you they’re working to get the scenes as good as they can. For the time and everything else, it just makes the whole environment different, and that’s that environment I want when I make films.

Q: There’s a great shot in this film of a carriage hitting a log and flipping over, doing a 360, and landing on the wheels. Was that practical or CGI?

Solomon: No, that was real, that was a stunt. We rehearsed it without all the chassis on the carriage, just with the actual skeleton, about forty times and videotaped it. About ten percent of the time it actually did the full flip and landed right side up, which is what I wanted. The day comes with shooting, everything’s there: the real horses, the piston, the guy’s on the carriage, and eight cameras. First take, it does a full flip and it lands right side up. That’s when you’re lucky because you just didn’t know; because it’s different every single time that thing goes, because you’ve got a four thousand pound piston going boom, propelling it in the air.It’s actually hitting that tree, it’s a real tree. Those guys are on it, you have to release those horses that instant so they can jump because otherwise when that carriage goes over its gonna be a train wreck because it’ll land on the horses; no more Gladiator horses. That’s what they were, the ladiator horses. That would be the end of that. And the guys needed to jump off and hope that they clear so that the carriage doesn’t actually land on them but they didn’t know which way it was actually going to go. Is it going to go left, is it going to go right, is it gonna go this far, that far? You don’t know. So it was all done realistically, I mean completely really.

Q: That’s a great stunt. Where did the idea come from?

Solomon: I wanted to show that there was no way to escape this thing. I mean there were a lot of different examples in the real stories about the witch in the twenty books [I read] and how they couldn’t escape – it would always find them and stalk them. So I came up with something like that, that was sort of an extreme example but that happened to be repetitive in showing the same theme, point over and over again. I just thought that was a great moment to do that with.

When I wrote the whole thing I envisioned the shot I was like, ‘OK, I’m going to do this shot with no cuts, no cuts at all. I’m gonna use CG going through the walls so that I can seamlessly put it together but basically from the moment it goes off her in the carriage and transitions into her bedroom and the bedroom is empty, there’s no cut until it actually hits the tree and the explosion happens and the tree falls down.’ All that is about thirty-eight shots, seamlessly put together making over a minute of film. I wanted it to be that way because I was trying to create what it looks like when you’re a spirit. When you’re going through walls and if you’re traveling at that kind of speed, for the audience look at it through a spirit’s point of view. Because I haven’t really seen that.

was trying to create what it looks like when you’re a spirit. When you’re going through walls and if you’re traveling at that kind of speed, for the audience look at it through a spirit’s point of view. Because I haven’t really seen that.

I’ve heard some comments subsequently about Evil Dead, which I’ve never seen, so if there’s any similarity there it’s not purposeful.

Q: Have you had any personal experiences with the supernatural?

Solomon: Personally, thankfully no. But I’ll tell you, recently – and I’m not making this up so you guys have a good story by the way. So, you know, the Bell Witch was known for pulling the covers off the bed, one of the most famous things right to the end of the bed. We have two guestrooms in our house in LA and I come home when I got off four nights ago, and my wife’s already been telling me, ‘OK, the guestroom door flew open about a week ago and the alarm went off,’ and whatever else. Now, we have our deck outside the guestroom door completely under construction because it got flooded. So it’s not open, it’s bolt locked shut and on the outside of it is actually sheet wood covering it up. There isn’t anybody getting into it opening it up, and it flew open. The front door flew open a different day; the dogs started barking at something. This was a couple of weeks ago. She brings it up a couple of days ago and in the guestroom, where the bed’s always made because nobody’s been staying there, the sheets – the duvet – is at the bottom of the bed. She just freaked the hell out on me, I was speaking to her on the phone last night, she’s like ‘There’s noises coming from upstairs.’ I don’t know, I went into the room and I did get the chills around the neck but I think just because I was psyching me out. I mean, you know, there’s been nobody there. I know, you’re all looking at me ‘Yeah right.’

Q: The Bell Witch is a classic supernatural story. As a filmmaker, how close did you feel you needed to stay to the legend?

Solomon: Well, I thought I was actually pretty good in putting a card up at the end that said this was just one version of how it ended and not the only version, because I thought that it was my responsibility to say that as a filmmaker. And thank God I did too because I screened it in Tennessee in Nashville, and we’re doing a Q & A in front of five hundred people and this guy stands up; I guess he’s about sixty-five and he says, ‘I’m Carney Bell, the great-great grandson of John Bell.’ I’m thinking ‘Oh shit.’

You know, like five hundred people, everybody claps for him, OK, a big standing ovation and this big pall of silence and then he announces he loves the film. I think to myself, ‘What are the chances? Based on what my film said about his family – and he wasn’t the only Bell there was like twenty of them. And there’s a CBS, NBC, ABC, filming this live. He said he loved it, it was how he imagined it with his having grown up with this legend. And he thanked me for putting that card on there.

As far as staying away from, I stayed true to what I saw consistent in the books I read. Not just Monahan’s book, not just the ending, but you know, what happens to Betsy, what happens to John, the things that they saw on the farm; the voices. I didn’t go as deep into the speaking of the Bell Witch and I didn’t touch on Andrew Jackson [who supposedly investigated the case] just because it didn’t fit into the screenplay I created. It would have seemed too like I was trying to validate how true this story really is if I’d put the Andrew Jackson scene in there because it just didn’t fit. I had a draft of the script I tried to put it into, it sort of wound away from where the whole story was going, it didn’t seem natural anymore, so I said to myself ‘Although it’s cool, sometimes even though its cool, if it doesn’t fit, you shouldn’t put it in.’ Instead I did a little internet episode that we have out there that talks about Andrew Jackson and the legend.

But I stayed true to the basic things that happened that were consistent in all the stories, whether it was told in Ingram’s original version or in one of the versions done just as early as two or three years ago.

Q: The UK and the US cuts are drastically different films.  Solomon: It was actually the critics and the audience at AFI that helped me realize what some of the flaws were in the first version. And because I started to think to myself, ‘If ten of the ten people say the same thing, and especially after my Dungeons and Dragons experience, its going to be a hundred thousand of a hundred thousand people.’ They’re pretty much going to s ay the same thing – maybe ninety-nine point nine nine nine nine nine. They can’t all be wrong. So I think if you can do it, you should do it and I luckily got myself into a position where I could do it.

Solomon: It was actually the critics and the audience at AFI that helped me realize what some of the flaws were in the first version. And because I started to think to myself, ‘If ten of the ten people say the same thing, and especially after my Dungeons and Dragons experience, its going to be a hundred thousand of a hundred thousand people.’ They’re pretty much going to s ay the same thing – maybe ninety-nine point nine nine nine nine nine. They can’t all be wrong. So I think if you can do it, you should do it and I luckily got myself into a position where I could do it.

I took some of the bigger things that I kept hearing and sort of put them together as a set of notes that I made myself and also from individual conversations and Q&As at AFI and from friends who saw the film. And then I stayed away from it for like two months. I just totally didn’t think about it. I just stayed away from it and then when I started the New Year I said to myself ‘OK, now I’ll go back to it.’ And I had the distance and with those notes to now look at it with fresh eyes and went, ‘You know what, that stuff is right, and now I can fix it.’ Because I did have the material, it was just choices that I made in the first place that weren’t necessarily the right choices. Again, your job is to make what you love as a filmmaker, but also you’re making the film for the audience mainly. You want it to be as good for them as possible, as enjoyable for them as possible, and as many people to like it as possible.