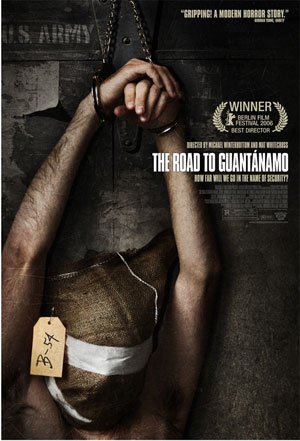

Possibly the only thing more amazing than Michael Winterbottom’s prolific filmmaking is how good these films often are; he’s not turning out random pieces of crap, and even when the films don’t work, they’re usually worth seeing (except for 9 Songs. God was that terrible). This year Winterbottom has the distinction having directed two of the best movies I’ve seen – Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story and now The Road to Guantanamo.

Possibly the only thing more amazing than Michael Winterbottom’s prolific filmmaking is how good these films often are; he’s not turning out random pieces of crap, and even when the films don’t work, they’re usually worth seeing (except for 9 Songs. God was that terrible). This year Winterbottom has the distinction having directed two of the best movies I’ve seen – Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story and now The Road to Guantanamo.

Guantanamo is provocative and harrowing, and scariest of all, true. It’s the story of the Tipton Three, young English Muslim men who go to Pakistan for a wedding, head to Afghanistan at the start of the American bombing, and find themselves held prisoner in Guantanamo Bay for three years, where they are tortured and seem to never have the hope of getting out. Or even getting a trial.

Winterbottom mixes talking head interviews with the real Tipton Three with dramatic recreations shot in Pakistan and Iran. The Road to Guantanamo manages to be a political statement and a work of art, but it’s not one that will be readily accepted by some Americans who refuse to see that there is anything wrong with their nation torturing and illegally detaining people. Yesterday I met with Winterbottom in a Manhattan hotel, and I wanted to get his answers to what I know will be the most prevalent critiques of the film.

Q: By the end of the movie we see a different side to the Tipton Three – these kids have criminal records, and it’s actually those records that help get them out of Guantanamo. But their records also make you wonder about why they really went into Afghanistan in the first place, and the film never addresses that…

Winterbottom: In the film they say really clearly why they go. First of all, they go to Pakistan for the wedding. They met up in Karachi, they were going to have a few days holiday beforehand. They went to a mosque and the Imam was saying, ‘You should go to Afghanistan to help your Muslim brothers.’ They went there on that basis to help. It’s impossible to prove one way or another – maybe they went there for adventure. They’re teenagers, it sounded exciting. What they said at one point in the thing is that they went because it was only two pounds fifty to go all the way – that’s a really cheap rate to go to another country.

That’s what they said. People who criticize them say right out that they don’t believe them – but why is that? For instance, in the war in Yugoslavia, a lot of British people went over to Bosnia to deliver clothes, to try to help out. People who were not Muslim. Everyone assumes that was true, everyone was like, ‘That’s fantastic, helping out, taking that risk to help people.’ It seems to me that underlying the ‘I don’t believe them’ is that if you’re young and Muslim, you must want to fight. That’s a pretty damning assumption to make.

Q: Do you think a lot of people are making that assumption? Do you think it’ll hurt the film?

Winterbottom: That’s the heart of the film. What we show in the film is very much them telling us what happened. They got to Kabul very quickly, in two or three days from Karachi. There wasn’t much that they could do there. They were very young, they didn’t speak the language – none of them could Pashtun or Urdu so they couldn’t speak to anyone. It would be like you going there. They were in the middle of a war, bombs dropping everywhere, they wanted to get out of that – but how do you get home when you’re in that situation? Its’ a very poor country that’s being bombed and you can’t talk to anyone – there’s no easy way out. They went to the people they traveled from Pakistan with and two of those guys could  speak some Urdu. They said, ‘Look, we want to go back to Pakistan,’ and they paid to go back to Pakistan. Instead they got brought to Kunduz. Kunduz was already surrounded by Northern Alliance and it would be impossible to get back from that point – at that point they’re trapped. And it’s all happened in only six weeks, it’s all happened very quickly.

speak some Urdu. They said, ‘Look, we want to go back to Pakistan,’ and they paid to go back to Pakistan. Instead they got brought to Kunduz. Kunduz was already surrounded by Northern Alliance and it would be impossible to get back from that point – at that point they’re trapped. And it’s all happened in only six weeks, it’s all happened very quickly.

In terms of Guantanamo and what’s happening there, even if they went to Afghanistan to fight, even if they went to pick up a gun… worst case is that they went to pick up a rifle to help protect people who were being bombed. I don’t see how even that justifies what happened in Guantanamo. Of course you can never prove people’s motives, you can never prove why they got on that bus to help out. But even if not, then what? What’s the argument then? Therefore Guantanamo is OK?

Q: Speaking of motives, what were yours? When you started this film was it with the idea of the movie making a difference in closing down Guantanamo? Can a movie make a difference like that?

Winterbottom: I don’t think a film can do it by itself, just like one newspaper article can’t do it or one TV report can’t do it. But yeah, the idea was that if we made the film, it would remind people that Guantanamo existed. At the time that we were making the film, things had gone pretty quiet about Guantanamo. It was no longer so much of a news story, but there were still hundreds of people there. So the idea was to remind people about it, remind people that there were prisoners who had been there four years with no prospect for any kind of legal recourse.

And things have changed. Not just because of the film, of course, but when we showed the film at festivals there had never been any British criticism of Guantanamo – we had been your biggest allies in this war. No one had ever said anything bad about it officially, but since then a number of Cabinet members, including chief legal officers and the Attorney General and the Lord Chancellor have said that it should close, it’s illegal. They said it helps recruit terrorists rather than hinder them, and it’s a stain on America’s reputation. In Britain there’s been a big shift, and now even George Bush is saying he wants it to close.

Q: Do you think he really wants it to close, or is this something to help in the midterms?

Winterbottom: I don’t know, but presumably if he is just saying it, he’s saying it because a lot of Americans want it to close. For us it’s important to show the film to an American audience. The thing most likely to get it closed down isn’t if the people in Pakistan think it’s a bad thing, it’s if the people in America think it’s a bad thing.

Q: In the scenes at Guantanamo you show both sides of the American soldier – some who are absolute assholes and abusive and some who seem decent. Was it important for you to show that?

who are absolute assholes and abusive and some who seem decent. Was it important for you to show that?

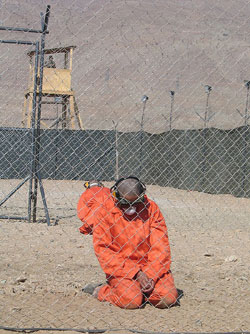

Winterbottom: I’m not an expert. We have Ruhel, Asif and Sahfiq talking about it – we have hours of tape – and it was very much a fact that they don’t have any hostility towards Americans. In fact they would love to come here, and they were going to come [for the press tour] and then they got too nervous about coming. And they weren’t hostile to the people who were holding them – in general. As you said, some of them were bad and too aggressive, and some were not so aggressive. But the point of the film wasn’t, ‘Oh the soldiers have gotten out of control,’ this isn’t an Abu Ghraib thing about them abusing the system. What we show in the film are the things that the system intends to happen. The things that were most difficult – isolation, extreme temperatures, stress positions, short shackling – these are all part of the accepted techniques of interrogation at Guantanamo. But these things aren’t even what’s most important. The most important thing is that Guantanamo shouldn’t be there in the first place. The only reason you have a prison in Cuba in the first place is that they’re trying to dodge international law – since these people should be prisoners of war – and American law, because you wouldn’t be allowed to do that here. If George Bush and Donald Rumsfeld think this is a good idea, and that this is a good place and a fair place, then it should be in America so that can be shown in the courts.

Q: Outside of porn and the most avant garde art filmmakers, you and Takashi Miike might be the most prolific directors today. Why do you work so much? What drives you?

Winterbottom: It’s more fun making films than not making films. From a work point of view, the worst period when you’re working is when you’re not working on a particular film, because you’re always going around trying to get money. There are always two or three things I would like to make, so if I’m not making one it means I’m just running around trying to get cash to make one, and that’s much less enjoyable.

Q: Do you work fast?

Winterbottom: It depends. There are different phases, and different films have different paces. With this one we met the guys almost as soon as they got out of Guantanamo, three or four weeks afterwards. That was about May 2004. We finally showed it at Berlin – and we  were literally rushing to get it finished – it took almost two years. The beginning of the process was telling them, ‘If you want to tell your story, we’ll get it on film.’ It took them three or four months to decide whether or not to do it. Matt [Whitecross], the other director, spent about a month living with them and then getting the research material together. We then started about March or April 2005 working on it full time. First we did interviews, then we had a small crew filming in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The film itself was relatively fast. But the editing, especially on a film like this without a script where we shot a lot of material, the editing is relatively slow. You have so much material afterwards that the first two months is just trying to sort through the material before you even start cutting the film.

were literally rushing to get it finished – it took almost two years. The beginning of the process was telling them, ‘If you want to tell your story, we’ll get it on film.’ It took them three or four months to decide whether or not to do it. Matt [Whitecross], the other director, spent about a month living with them and then getting the research material together. We then started about March or April 2005 working on it full time. First we did interviews, then we had a small crew filming in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The film itself was relatively fast. But the editing, especially on a film like this without a script where we shot a lot of material, the editing is relatively slow. You have so much material afterwards that the first two months is just trying to sort through the material before you even start cutting the film.

Q: What genre is this film? Docudrama doesn’t seem to cut it.

Winterbottom: I don’t like docudrama – I hate the phrase anyway. But we were deliberately trying not to dramatize. These guys were telling their story; they were narrating the story and we recreated the bits we could recreate to make it easier to understand and to make it more vivid. And just to get across more information – you show people the mountains of Afghanistan where they were and you get more sense of what it was like than if you just described it. We certainly tried to avoid fictionalizing it. We tried to avoid making characters. We tried to avoid having dialogue scenes, we tried to avoid all the stuff of drama and just say, ‘This is what happened.’ So I don’t know what you would call it.

Q: In a lot of ways it’s like United 93. Have you seen that?

Winterbottom: Yeah.

Q: Do you think there’s sort of a movement going on here, where more filmmakers are going to be approaching movies in these zone between narrative and documentary?

Winterbottom: Yeah, I think… part of it is being informed by as technology gets smaller and simpler it’s more tempting to put your fictional people in an uncontrolled, real situation, because you can get away with it more. There’s something inherent in film anyway, as a medium, where even if you’re in a totally fictional situation there’s one side of it where you’re recording something that happened. You’re always in the area between recording something real and making the fiction of film. So yeah, I think there are lots of people now who seem to be working somewhere that more obviously has – it’s not quite fiction, but it’s less controlled, perhaps.

The hardest part about this was, compared to a movie like In This World, which was essentially fictional and we could do what we wanted to do, this was a situation where we didn’t have that freedom. We had to stick to what they told us; we couldn’t think, ‘This would be interesting.’ If it didn’t happen, we couldn’t put it in. Everything you see in this film comes from what we were told happened.

Q: In This World is such a devastating movie, and even though it’s not factual it feels completely true. Does something have to be factual to be true?

Winterbottom: There’s all sorts of different areas and you can use truth in all sorts of different ways. I’m going to avoid that question, but certainly there’s a big difference between this film and In This World. With In This World, those really were Afghan refugees, and we talked to lots of people who really had done trips like that, but we were free to organize the journey. And then we were free to pick up things that happened on the way, and then we organized things to happen as well. Some of them were found by chance and some were organized, but hopefully by the end of it all, you feel this is something with truth in it, there’s something honest about what we showed. That this is what it must be like to be a refugee trying to get to Europe.

With [Guantanamo] it is the opposite of that. Because we have to stick with what they told us happened, it can almost be seen as less ‘true,’ because instead of someone reacting in a way that feels right, they have to react in a way based on what [the real people] did. Just to clarify, the Road to Guantanamo was very factual.

Q: Tristram Shandy was one of the funniest movies I have seen in a long time. What’s up with the American DVD release?

up with the American DVD release?

Winterbottom: I assume it’s coming out quite soon. It hasn’t come out anywhere yet, but there’s one coming out in the UK quite soon. When we shot the film, because of the nature of the film, there were lots of things that were always intended to be on the DVD. We did a rough edit of about an hour and a half of parallel scenes or alternative versions of scenes, things which would have a Shandy-esque relation to the story. But whether they put it on or not I don’t know, it’s unfortunately not an area we control. But hopefully all that material is on, because there’s a lot of nice stuff on it. And as I say, it has a kind of integral connection to the book. The idea was to do it like footnotes, to go off on a little diversion, and then come back in. The idea is that the DVD would have more of the texture of the book than the film did, which was actually quite simple.

Q: Next you’re doing a ghost film and an Uzbekistan film?

Winterbottom: There’s a couple of things. There’s also one possible thing back in Pakistan, and I think the Pakistan thing might go first. I was going to do the ghost story in Italy, but then the Pakistan one happened. So we may do that first.

Q: What’s that about?

Winterbottom: I’m not supposed to talk about it, which is kind of pathetic!

Q: And the Uzbekistan one you’re doing with Steve Coogan?

Winterbottom: It’s a true story. The ex-British Ambassador just released a very funny account of his experiences when he went to Uzbekistan.

Q: I didn’t know it was funny.

Winterbottom: It’s a very funny book., but it’s about torture. We’re making a funny movie about torture. It’s sort of Dr. Strangelove meets torturers.