When 52 Equals Zero

By Devon Sanders

It happened last week, just a few short days before America celebrated the Martin Luther King, Jr. national holiday.

DC Comics announced the cancellation of six of the books launched in their “New 52” initiative. With the cancellation of two of their titles, 100% of comics writers of African descent, Eric Wallace and Marc Bernardin of Mister Terrific and Static Shock, respectively, were laid off.

OK, let’s get this out of the way. I’m not asking for quotas. I am NOT crying racism. I’ve seen racism and this definitely ain’t it.

Racism takes a bit of forethought, malice and more ignorance than should be devoted to anything. What this is is simply a glaring gap, a gaping hole I simply don’t see either of The Big Two looking to fill any time soon.

I realize there are a number of talented people of many colors doing many different jobs within the comics industry but damn, no matter how you look at the number, it still comes down to ZERO. This number does not reflect malice or lack of consideration, it is simply this:

The writer, the name you first see in the comics credits, the person who usually creates the story is vastly important and yeah, there’s now ZERO presence.

Why is this? Comics titles are launched all the time and it seems that not a day goes by lately where you don’t hear about some title’s cancellation. The answer always comes back to low sales. No matter how “critically acclaimed” a title, no matter how many favorable reviews, if it isn’t selling it’s open to cancellation. What the cancellations of these two titles does is point out the importance of familiarity to the comics market.

If it ain’t what the greater comics market knows or wants, it gets left to the wayside.

Nowadays, not even a Bat, Green Lantern or Superman symbol can save a character from obscurity. Until recently, had anyone seen much of Steel? DC, over the years, inexplicably lowered the profile of their most prominent character of color, Green Lantern John Stewart by having him take a backseat to Hal Jordan in all of their media. All in the name of branding to a greater audience that would’ve responded to strong storytelling featuring ANY Green Lantern.

The market, as it stands, will not respond to Mister Terrific or a Static Shock unless it speaks to them. The numbers bear this out, as well. Terrific was doomed almost from the start. Artistic changes were made before the book even launched. The fact that the character was cut off from The Justice Society, the very thing that made him prominent, didn’t help things at all. Add this to the mix and any writer outside of a Grant Morrison would have a hell of a time selling this to readers.

Also, the perception that these books were afterthoughts and pandering from inception may have had something to do with it as well.

Another factor also could be the bassackwards way writers come into the industry, nowadays. In order to be considered by The Big Two, one has to work OUTSIDE of the system before being considered. Reginald Hudlin had to direct movies and become one of the heads of a major cable network before being asked to write Black Panther.

Last year, the comics industry lost one of its greatest minds, writer Dwayne McDuffie.

I’d first discovered him as the writer of Marvel Comics’ Damage Control mini-series. In an era when every creator seemed to be taking comics by the hair, kicking and screaming, down a dark alleyway, here was this… thing. This very funny… thing. A comic that asked and answered the answer, “Who’s gonna clean up this mess?” It was brilliantly written and vibrantly drawn and honestly, a breath of fresh air in an industry hell-bent on becoming hell-bent.

McDuffie, tired of the Luke Cages and Night Thrashers of the comics universe, co-created Milestone Comics, a brand formed on the knowledge that characters of color and even different sexualities could and should have just as many chances at heroism as anyone else. From this, we got The Blood Syndicate, The Shadow Cabinet, Xombi and the books he personally wrote Icon, (and more important to me, his sidekick, Rocket), Hardware and yes, Static. Static would later go on to receive his own long-running cartoon series, Static Shock. (McDuffie wrote many of its episodes.)

McDuffie went on to write many more cartoons, chief among them, Justice League Unlimited, the Super Friends cartoon many wished for as adults. Watching this show was seeing everything you loved about comics rendered big on screen. In each McDuffie script, you just knew he adored the material he was writing about and it showed in every word.

Only after making his name to millions through writing for animation did McDuffie found his way back to comics’ tens of thousands.

One of comics’ greatest writers had to leave comics in order to work on Justice League for DC Comics.

I just can’t accept that as awesome as all of writing is, there will be ZERO black superhero writers being published as of May 2012.

DC. Marvel. Everyone.

We need better. I want to feel like anyone can be included in all facets of the creation of comics.

I simply believe there can always be better than zero.

Planet of the Apes #10 (Boom!, $3.99)

Planet of the Apes #10 (Boom!, $3.99)

By D. S. Randlett

If any of us are being honest, we really didn’t see this series coming. The newish Planet of the Apes ongoing began a few months before last summer’s Rise of the Planet of the Apes hit theatres, when we really didn’t know what to expect of this franchise as it poked its head up as if after a long nap. Both the comic and the film made their respective cases admirably. Not only is this franchise capable of still churning out good yarns, it’s telling stories that feel like they matter. If Rise is the document of a young social movement asserting its rights, the Planet ongoing is the story of a culture struggling with the conflict between the ideas and ideals at the center of its inception and the demands of history’s cruel marching.

While ideas are at the center of this series, strong writing and great art have been the order of the day. The characters all have unique voices and outlooks on their contexts. There are no real bad guys here: both the Ape and Human characters are written as people trying to keep it together in an impossible situation while trying to hold on to their ideals, their beliefs, and those that they love. Of course, as everything spirals out of control, how will they be able to hold on to anything?

The tenth issue of this series marks a turning point of sorts. The riots of the first arc have escalated into something that could conceivably be called war if it weren’t so one-sided. The Apes, led by General Nix, have very little trouble hunting down a contingent of humans, who have abandoned the city of Mak. The turning point isn’t so much in the plot, as it is in the reader’s relationship with General Nix. Before this issue, the albino gorilla has been presented largely as a stoic soldier who is very good at carrying out his duty. The writer seems to understand that stoicism is often a cover for sorrow, and this issue brings that out a bit as we see some of Nix’s recollections of a crucial crisis point in the relationship between Apes and Humans, recollections which connect him to several other characters, human and Ape.

At this point in the series, the scope of the book is also opening up a great deal as contingents of humans flee for the mountains and the war between the species continues to escalate. Planet of the Apes is proving itself extremely adept at balancing the issues of social justice at the franchise’s center with a plot that is getting bigger in terms of its scope, yet more incisive in terms of its characters.

Planet of the Apes represents some of the best aspects of political sci-fi and fantasy, and it remains a series well worth your time.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

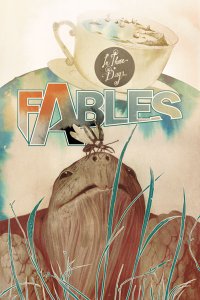

Fables #113 (DC Comics, $2.99)

By Bart Bishop

I’ve been out of the Fables loop for a while now. The series, which began in 2002, has been a favorite of mine since the beginning but somewhere around The Great Fables Crossover (with Jack of Fables, from 2010), I lost track. The expansion of scope these last few years is not unwelcome, as series such as The Literals and the upcoming Fairest show a wealth of creativity and imagination on Willingham’s part, but I’ve always felt that once the Adversary was defeated that Fables proper should end. When new threats were introduced, it felt like nothing could ever compete, much like any new Star Wars tale will always be living in the shadow of Vader, the Emperor, and the Death Star.

If so hesitant, then why did I pick this issue up? Well it’s standalone, titled “In Those Days”, featuring “fan-favorite Fables characters in idyllic other times and places!” This was appealing to me, the casual fan, and I’d also recommend it to any new readers as a fun jumping on point. It manages to straddle a fine line, filling in the gaps of obscure bits of continuity while making the whole thing feel insular and accessible. There are four short stories here, preceded by a brief introduction, all written by Bill Willingham but a different artist for each story: “A Delicate Balance” by P. Craig Russell; “A Magic Life” by Zander Cannon and Jim Fern; “The Way of the World” by Ramon Bachs; and “Porky Pining” by Adam Hughes.

The introduction is nice in concept, with a travelling performer working as the framing device as he appears to be the one that tells these tales, but ends up feeling disconnected from the rest. Why the reference to Rose Red, and is this performer actually telling the tales or acting them out? Some interconnection between stories would’ve been nice. The stories, as well, lack variety: three of the four deal with the implications of a powerful spell being cast. This could’ve been used for insightful juxtaposition, but little thematic connection is made. Anthology tales should try to accomplish one of two goals: either approach the same topic or theme from different perspectives, or have vastly different tales. This issue, unfortunately, fails to do either.

As individual short stories, however, they work very well. My favorites were the first and third, and it doesn’t hurt that the latter story feels the effects of the former. “A Delicate Balance” has a king punish his adulteress wife by turning her into a turtle and placing the queen’s homeland upon her back in a teacup. Very whimsical, and bizarre enough to make the Brothers Grimm proud. What are fables if not parables to teach us lessons? The lesson here is in humility and responsibility, while taking a moment to philosophize about the questions of souls and sin. Russell’s art is one-part children’s book, one-part Renaissance painting. I love him and his style, reminiscent of Charles Vess.

“The Way of the World”, meanwhile, is a very simple tale but has a lot to say about childhood wonder and the crushing simplicity of adulthood. A young boy and his father, who live inside the teacup on the back of the turtle, sail to “the edge of the world,” the wall, as a rite of passage. It’s only three pages long but it gets to the point, as the father and son find the heart of religion: he and the boy debate their existence, with the father’s views contrasting against the boy’s teacher at school. They’re both right, in a round about way, but what it gets down to is acceptance. The father accepts not knowing and the boundaries the wall represents, whereas the puerile boy strives to know what’s beyond the wall. Very apt, and speaks volumes about how humanity’s attempts to rationalize what it can’t fathom.

“A Magic Life” isn’t quite as effective, as it’s striving for a irreverent tone but doesn’t go far enough. It’s also a bit of unnecessary retconning: I never questioned the security of the citizens of Fabletown before, why provide answers that didn’t occur to anyone before so after the fact? Still, Kadabra is a compelling lead (although the end rushes to show what must be past events from the series proper, events I am unfamiliar with). The art by Cannon and Fern is a bit awkward, with the human form appearing overly boxy and gangly, but it’s never unclear. “Porky Pining” (hah, cute), however, has breathtaking art by Adam Hughes. The man never fails to deliver, with intricate detail and beautiful designs like that of an ancient tapestry. No one in the industry draws women like Adam Hughes, which is appropriate here as we must be as convinced as the Porky Pine about the validity of his lust. There’s also a clever phallic subtext dealing with the quills of a porcupine that’s not dissimilar to mythological legends and tales of human beings copulating with animals.

What can be said about the cover by Joao Ruas? I want this as a poster. I want to buy a van so this can be painted on the side. Fables has a long history of evocative covers, and this induces a sense of awe and serenity to rival any of them. The seeming smile on the turtle’s face is cracking me up, and what’s even better is the sense of melancholy that taints it once you’ve read the story inside.

What more recommendation can I give? When my girlfriend saw the cover and I described the series to her, she replied, “I’d read that.” This is a woman that had no prior experience with comics before me, and even now has only read a few graphic novels (Blankets, Coraline) I suggested. That’s really the strength of Fables; how it takes the familiar and subverts it, guaranteeing an in for non-comic book readers while telling fresh stories. There may be more sex and violence than the Disney adaptations, and more snark and post-modern malaise than the original fairy tales, but Fables always manages to stay true to the spirit of both while doing its own thing.

Plus it’s 32 pages for $2.99, which is easy on the wallet.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Dead Man’s Run #1 (Aspen Comics, $3.50)

Dead Man’s Run #1 (Aspen Comics, $3.50)

by Graig Kent

Dead Man’s Run, if you don’t know the conceit in advance, is a truly bizarre read. It opens in the aftermath of a maximum security prison riot. Laying dead on the ground of the prison yard inexplicably under a pile of gold bricks is decorated army captain Frank Romero. Back in the civilian world Sam Tinker learns that his boss (the same Frank Romero) is now dead and, with the threat level still high, his concerned younger sister, June, picks him up. presumably to evacuate him from the city. They don’t make it very far before they are t-boned by, well, a tank.

Sam wakes up in a state of delirium, or so it seems, envisioning a series of nightmarish situations, one flowing into the other, all of it seeming so real, until he encounters Frank Romero in a twisted prison maze who explains that Sam was brought there to rescue him. Sam, a brilliant cartographer, determines that he’s essentially in highly conservative interpretation hell, but also that he may be the only one to escape it. Of course, June may be there as well, and he’s got to find her first.

Had I known the concept of the book (which in hindsight seems pretty plain given the title) the first read would have been a lot less confusing, and indeed, a second read through proved a lot more intriguing. Coming from big-time film producer Gale-Ann Hurd’s Valhalla Entertainment it’s obvious that this is a treatment for something destined for a modestly budgeted big screen production. Written by Greg Pak, best known for his work on The Hulk, it’s a solidly written story, littered with little curiosities (if not flat out mysteries, like: What’s up with those gold bars? Who’s the phantom woman? Where was June taking Sam at the start? What’s up with the warden?) that beg for more explanation. There’s very little character work done here, so it’s hard to really invest in Sam at this stage but the situation and the task before him certainly command some interest.

It’s a fast-paced, surprisingly fluid story from Pak, and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep artist Tony Parker does a solid job conveying all the intricacies seeded in the script and capturing the flow. Parker’s a young talent and it’s easy to see he’s still developing, with uneven weight to his lines from panel to panel and inconsistent renderings of characters form page to page. Some pages are far cleaner than others, and that style works better than when he’s heavy with his shadows. He’s spare in his detailing, particularly background details, which is hopefully something he can get over to really help build the visual environment of this “hell prison” he’s creating.

I’m not certain if this is a mini-series or ongoing, but it does seem to lean towards the former. If it is an ongoing Pak definitely seems to have some ideas in place for it. A solid start that may be worth closer attention if it continues to hold strong as it prog

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Danger Girl: Revolver #1 of 4 (IDW, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

One reason that superheroes continue to hang on in comics is the ease with which a good visual artist can convey the impossibly spectacular actions and abilities that we associate with these godlike beings. Not even the best Hollywood special effects team can depict flight, super-speed, or the like, with the ease of a Romita or Immonen: on film, you’re almost always aware of the effort that went into the creation of the effect. It’s a little different when it comes to the staples of the “action” film: few of us have ever been involved in car chases or shootouts, but they’re grounded in elements that are mundane and recognizable, and our eyes and ears can be fooled more easily into accepting that sort of FX trickery as “real.”

Which is one of the challenges that the Danger Girl spy-adventure comics have always faced: even the most skillfully rendered comic-book vehicle chase can feel a bit pale next to its big brother in, say, the latest “Fast and Furious” installment. But give the art team of Chris Madden and Jeromy Cox credit: the first 18 pages of Andy Hartnell’s script are a kitchen-sink of transportational possibilities (including boat, seaplane, motorcycle, double-decker bus, and horse), and they bring about as much kinetic energy to the visuals as you could ask for. And, since this is a Danger Girl comic, there’s a Macguffin, snappy patter, nasty foreign-type bad guys, guns, swords… and, through all of this, Abbey Chase managing not to fall out of her wedding dress (don’t ask) costume (in a film, you’d have had to glue the thing in place to get it to stay on her).

It’s actually all a “pre-credits” sequence, as the last few pages begin the story proper with Deuce (the Sean Connery standin who serves as the team’s Charlie) giving the Girls their next assignment, which comes with both an unwelcome guest and an uncomfortable target.

When you read a Danger Girl comic, though, you can’t help thinking that all of the elements that are borrowed, lifted, or analogued from other media add up to a good deal less than the sum of their parts when confined to the comics page. The level of characterization retains the sketchiness of a B-action movie (Abbey’s determined and plucky; Sydney’s cheerful and saucy, etc.). And for those who mostly read (?) for the fan service, it’s worth noting that Madden and Cox treat the titular Girls with the same sharp angularity that they bring to boats and blades: for better or worse, Scott Campbell knew how to make a ludicrously proportioned butt or tit look more or less like part of a human being.

If you’re already a Danger Girl fan, add a star to this review. If it’s your first exposure to the property, this comic is certainly a less expensive way of letting you quickly decide whether or not it’s your thing than investing in one of the trade editions.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Batman #5 (DC Comics, $2.99)

Batman #5 (DC Comics, $2.99)

By Devon Sanders

Wednesday morning, 8 a.m.

I check my e-mail, someone I truly respect writes, “Is Batman #5 misprinted or is it supposed to be like that? Take a flip and let me know what you think.”

Groggy, I read it. Seven minutes later, after reading it, I put it down and have not felt this way about a Batman comic in a very long time. For the first time in a very long time. I felt enthused. I felt genuine surprise and wonder. Yes, surprise. Wonder. In a comic.

One week following last issue’s events, The Batman, trapped in a seemingly endless labyrinth conceived by The Court of Owls, finds himself at his mind’s edge. Within the walls of the labyrinth, he finds himself alone, dehydrated and enclosed within near perfect dark. The World’s Greatest Detective is without a clue as to how to escape and as he goes over his plight, his mind begins to twist and turn and writer Scott Snyder and artist Greg Capullo, pull you, the reader, into his despair.

Through incredible narrative and page layout, Snyder and Capullo combine to show and prove the medium of comics is still very much a place for bold imagination and innovative thinking. With this issue, Scott Synder adds his name to my personal all-time favorite Batman writers, right alongside Alan Moore, Alan Grant, Ed Brubaker & Frank Miller. Good company to keep.

Artist Greg Capullo is doing some of the best work in comics. Capullo’s Batman truly is a man at the edge and it honestly hurt this Batman fan to see his favorite character broken so. What Capullo does, however, is provide through his art direction an experience so singular and memorable, I defy any reader not to feel something.

Batman #5 is truly one of my favorite comics to come around in a very long time. Not yet complete, I honestly believe Snyder and Capullo’s turn on Batman will go as a “definitive run.” Batman #5 is the rare comic that still has me buzzing days after I’d read it. I haven’t felt this way about a single issue since Batman: The Killing Joke.

I truly believe this issue of Batman will continue to occupy this space within my mind, as well.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Prophet #21 (Image, $2.99)

By D. S. Randlett

If you have ever read a comic book in your life, the absolute last thing that you should expect is that characters will truly ever lie dormant. A couple of months ago Prophet was a dimly remembered relic of a past when my dad would buy every number one that hit the stands during the speculation era. I vaguely remember wondering just what the hell the main character’s deal was, despite thinking that he kind of looked cool in a mid-nineties glowering, Schwarzenegger-esque sort of way (I was eight). Still, what were his powers? What was the gimmick, the story? Doing some background for this review didn’t yield very many soluble answers (there’s not even a Wikipedia page for this character at present), but I did manage to dig up some convoluted back story and inconsistent time travel powers. No wonder I favored Valiant back then.

Of course, the only thing that the twenty first issue of Prophet dredges up from the mists of memory is a title, a name, and a streamlined version of the time travel concept. Time travel is a bit of a misnomer here, as this John Prophet seems to be a mercenary who retreats into cryosleep between missions. The opening scenes of this book are fitting: a relic from another era comes up from the depths to discover a world greatly changed from the versions of it that he’s known.

Narratively, this issue seeks to do what most first issues tend to do, and does it rather well. There is more emphasis here on setting a tone and showing Prophet and his readers a new world. Sadly, the main plot doesn’t really kick in until the final few pages, but this is only unfortunate because I just wanted more. But, what is here is magical in the way that the best science fiction is.

Prophet, so far, has an incredible bestiary. If you’ve ever been to a good natural history museum, you’ve probably noticed how the best animal exhibits manage to tell the stories of the evolution of all sorts of animals. Something we could take for granted, like a whale or a bird, can become a profound story in its own right. Prophet is littered with strange creatures with strange biologies, and even the beasts that are shown or mentioned in passing manage to pass on vital information about this strange world and hint at the stories that make them up.

Many have compared this book to European scifi comics, and that influence can definitely be felt, particularly in Simon Roy’s artwork. There are hints of Hergé in the backgrounds, whiffs of Moebius in the characters. The colors by Richard Ballerman really make Roy’s work sing, and do a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of Prophet’s sense of immersion. On the other hand, the writing style feels very brutal, very terse. In other words, very American. Brandon Graham’s words, even though they don’t exactly echo those of Jack London, put the story into a very similar territory. The world presented here is tough and wild, and the narration really supports that.

Prophet is definitely a title to watch, and will likely be something worth remembering.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Steed and Mrs. Peel #1 of 6 (Boom!, $3.99)

Steed and Mrs. Peel #1 of 6 (Boom!, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

British TV had its “Avengers” a year or so before the comics did (and in both cases, the name was chosen not because there was anything that particularly needed avenging, but just because it sounded cool). It began as a low-budget show about a detecting (male) doctor who found himself mixed up with a mysterious secret agent. In short order, the doctor was set aside and the agent, John Steed (played by Patrick Macnee), moved his nattily-dressed frame to the fore, aided now by a sexy, athletic, ultra-capable blond knockout named Mrs. Cathy Gale (Honor Blackman), whose occasional forays into black leather set viewers’ imaginations off into directions far more kinky than anything that was actually happening onscreen. Over the next few years, The Avengers grew into practically its own genre, with outré mysteries and even the simplest plots laid over with a patina of the outlandish, with increased budgets allowing for some of the most intriguing visual storytelling anywhere in 1960’s television. Its villains grew more and more cartoonish, and even the incidental supporting characters were often wildly idiosyncratic creations more intriguing than the storylines they were involved with. James Bond became an influence, as did Carnaby Street, but no more so than, say, Agatha Christie, Saki, or P.G. Wodehouse.

By the time the show made its way to American audiences, Blackman had left for a film career (which never really advanced much past her role as Pussy Galore in Goldfinger), and Steed was now working in tandem with the karate-chopping Emma Peel (the original casting call insisted that the actress filling the role needed to have “m(ale) appeal”), played by a young actress from the Royal Shakespeare Company, Diana Rigg. Whether or not Blackman’s Cathy Gale would have captured American imaginations in the same way that Rigg did can never be known, but there’s no question that Emma Peel added a warmth and lightness to the smarts, competence, and independence that she shared with Mrs. Gale. When Rigg herself left for the movies after two series, she was replaced with Linda Thorson’s Tara King (too transparently shaped as a clichéd “swingin’ London bird”), and The Avengers managed one more series before calling it a day.

But it’s the team of Steed and Mrs. Peel that stands for the default version of TV’s Avengers for today’s audiences, and there have been occasional attempts to revive the franchise down through the decades (Macnee himself wrote-or perhaps had ghost-written, I suppose-a couple of novels about the pair’s adventures). And back in the early 90’s, a young(ish) Brit named Grant Morrison was given the opportunity to revive the team for the comics. With Marvel sitting comfortably on the name “Avengers,” the series was named instead after its two principal characters. Given that comics publishers outside of the Big 2 seem to be falling all over themselves to license properties from other media these days, I’m not surprised to see Steed and Mrs. Peel return to the comics… but I am surprised that it came in the form of reprints of a two-decades-old comic, even with Morrison’s name for marquee value.

The comic series is new to me, as I managed to miss it first time around, but even so, it’s not hard to get a sense of its vintage: artist Ian Gibson (The Ballad of Halo Jones) is working in a sketchy, caricatured style that is almost the polar opposite of the big, bold, Photoshop-heavy work that licensed properties tend to get these days. Added to that, Morrison’s touch is very light, with little of his personal stamp on the material: he’s crafted a faithful pastiche of an Avengers episode, with such touchstones as the absurd entrée into the inner sanctum of “Mother” (Steed’s wheelchaired boss who was introduced in the Tara King series), the quirky episode subtitles (“Steed breaks the rules / Emma gets a full house”), and Steed’s familiar invitation of “Mrs. Peel, we’re needed.”

In some ways, it’s an engaging piece of “what if” fan-fiction, as the storyline has Tara King disappear during an investigation, sending Steed to “reactivate” Emma Peel to help find her. The setup with Tara has her learning the usual bizarre elements of a mystery from an endearingly wacked-out sea captain. When he turns up dead, Steed goes into action, and Emma is soon investigating suspicious doings at a modeling agency… while kitted out in one of her form-fitting white catsuits. Morrison’s script throws in the kind of visually arresting background details that were typical of the TV series, and Gibson gives the human-headed chess pieces and life-size ship-in-a-bottle a sort of cheeky realism. His Macnee is pretty accurate (if a bit lumpy), and he gets Rigg’s face a bit better than Thorson’s, but the look of the comic is definitely geared more toward storytelling than simple reproduction.

One drawback is that breaking the comic series down into six issues (from the original three) means that this first issue has to carry a lot of expository baggage, so it’s awfully talky. Morrison and Gibson understand the strengths of the TV series well enough that future installments will likely rely on the sort of visually-arresting storytelling that marked The Avengers at its best (and would probably have prompted me to give it a higher rating). But I’m not sure that isn’t really an argument to try and hunt down the collected editions of the original comic instead.

Steed and Mrs. Peel does a good job at hinting at the elements of the original TV show’s strengths, but it does tend to point up how much the personal chemistry of Macnee and Rigg helped ground (and elevate) scripts that might otherwise be an unconvincing jumble of the mundane and the ridiculous. Not the place to start with this property, but for fans, a nice bit of nostalgia.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

SPECIAL DOUBLE-TAKE REVIEW:

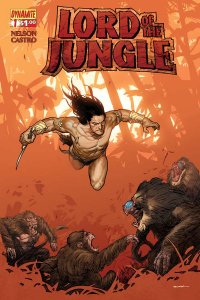

Lord of the Jungle #1 (Dynamite Entertainment, $1.00)

by Graig Kent

I’m not much of a Tarzan fan. I don’t see the appeal, but then, perhaps to my own disservice, I’ve spent precious little time exploring the countless stories that have been told with the character over the years. The whole “raised by apes” thing, the “Me Tarzan, you Jane” bit, the “Greystoke” family legacy aspect… all these little bits and pieces are known to me despite my apathy towards the character’s mythology, which tells how truly penetrating Edgar Rice Burrough’s character is in popular culture.

Lord of the Jungle is yet the latest adaptation of the character, this one promising (in its solicitations) ” For the first time in its 100 year history the classic Edgar Rice Burroughs story, Tarzan of The Apes is told UNCENSORED!” Now, I can’t say that this is a truer adaptation of Burroughs’ original story than any of the others, or yet another bastardization, as I have no expertise on the matter, but if by UNCENSORED they mean it’s brutal in its violence and unrelenting savagery, then sure, its a fair claim.

This $1.00 introductory issue is light on the dialogue and heavy on the theme of loss as it breezes through the first year of Lord and Lady Greystoke’s abandonment in a mysterious jungle, from their shooting of an attacking ape, to the slaughter and eating of a native jungle tribe by hybrid man-apes, the crushing death of Kala’s infant by her shrewd leader, to the death of Lady Greystoke post-birth, to the apes’ bludgeoning of Lord Greystoke, it is a brutal, brutal 22 pages of comic, but effective in establishing the dangers of the jungle and the savagery of its inhabitants.

Writer Avrid Nelson sets up the background of Tarzan quickly and quite effectively,if not utterly cleanly. A more assured narrative hand would have assisted with some of the confusion surrounding the passage of time, as is, the captioning is pretty bare bones. Just like the continued retellings of Superman’s origin, we kind of know all the broad strokes of Tarzan’s backstory, but it’s in the finer details that differentiate each iteration of the character. Artist Roberto Castro has a strong sense of detailing, and a curious and not unattractive style, partway between Denys Cowan and Howard Chaykin, however the clarity of Castro’s storytelling isn’t always there, particularly when the storytelling is all up to him. The gorilla sequence, though cleanly illustrated, is baffling from a motivational standpoint. Whether this is also a failure of the script or solely the artist, I can’t say, but I find myself scratching my head as to why the apes, particularly the king gorilla, are acting the way they do.

Next issue box tells of the arrival of Jane to the island, though given that this book ends on Kala discovering the naked ape, it seems the series might be breezing through the nurturing stage, heading straight towards the muscles and the loincloth (though there’s obviously plenty of opportunity for flashbacks as it is an ongoing series). There’s not a lot of wow factor here, but for a buck it’s a straightforward yet engaging introduction/reintroduction to the mythos of the character, if ever you were curious.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Lord of the Jungle #1 (Dynamite Entertainment, $1.00)

By Bart Bishop

Much like Graig, I wouldn’t call myself a Tarzan fan. As far as I can tell, I’ve never read an “official” Tarzan novel; that is, nothing written by Edgar Rice Burroughs. I haven’t even seen the Disney movie! I have, however, read Science fiction author Philip José Farmer’s Tarzan Alive (1972), which I highly recommend. Even with little firsthand knowledge, the character and his characteristics have become so familiar as to lose legitimacy. This is an icon that has been neutered into caricature; how to make him fresh again?

Written by Rex Mundi creator Arvid Nelson with art by Roberto Castro, this new series posits to heavily follow the original story of author Edgar Rice Burroughs (who also created John Carter of Mars, featured in comics published by both Dynamite and Marvel, and soon to be in a live-action Disney film). Much like Dynamite’s recent Flash Gordon: Zeitgeist, Nelson’s idea is to present a more pure and naturalistic (sigh, “grim & gritty”) Tarzan devoid of the family friendly clichés that Graig mentioned. The book is called, however, Lord of the Jungle due to the Burroughs estate keeping a tight rein on the Tarzan name, but there’s no mistaking the identity of the title character.

If anything the title works double duty, avoiding the silliness associated with the copyrighted name while providing an air of cultivation. The very first Tarzan novel, Tarzan of the Apes, was published as a book in 1914. Many sequels and iterations followed in book form, movies and serials, tv shows (animated and live action), and finally in comic books. Lord of the Jungle, therefore, follows in a long tradition. Tarzan was, in many ways, the first pulp hero (with Sherlock Holmes, in my opinion, as the proto-pulp hero), predating the likes of Buck Rogers and Conan by nearly twenty years. The pulps and their magazines set the stage for comic books and the superhero, so it’s fitting that the character that got the ball rolling is featured in this medium.

The story begins in (does the math) 1887. Lord Greystoke, who I was not aware before is actually named John Clayton, and his wife Alice, are left stranded on the coast of the Congo by a mutinous crew. Actually it’s unclear exactly why the crew abandons them. The Claytons must fend for themselves in this unknown jungle, and Lady Alice’s pregnancy certainly complicates things. What’s fascinating about all this is, discovered through a bit of Google research, Burroughs’s narrator in Tarzan of the Apes describes both Clayton and Greystoke as fictitious names, implying that Burroughs was actually documenting the true history of a real man but changing names to protect Tarzan’s identity. Fascinating.

The aforementioned Farmer’s Tarzan picked up on this idea, depicting the “real” person Burroughs based his character on. Farmer also staged the first major fictional character crossover, revealing that Tarzan is related to Sherlock Holmes and Doc Savage; this is known as the Wold Newton family, based around the idea that the (real) meteorite which fell in Wold Newton, Yorkshire, England, on December 13, 1795, was radioactive and caused genetic mutations of people nearby. Their descendants are highly intelligent and strong, and are prone to extremes of good and evil. What Farmer also injected into his novels was a healthy dose of sex and violence, to the surprise of the fans at the time. What this adds up to is this: edgier Tarzan has been done before. Is there anything new in Nelson and Castro’s interpretation?

Competent is the word I used when discussing this book with Graig. Nelson is operating in the school of Brian Michael Bendis, decompressing a classic tale in order to allow quiet meditative moments and extended action. He writes the Claytons compelling enough, although they border on being Mary Sues: why exactly is John “so handy” if, one assumes he’s lived such a life of luxury? Not that he couldn’t be, but even the character is surprised that he’s able to construct an entire house, alone, in just a few weeks. Why were the Claytons traveling in the first place? These are the little details that could flesh out the secret origin of Tarzan, but the reader is kept at a certain distance. Credit, however, must be given: Alice isn’t restricted to being a hysterical female, as even while barefoot and pregnant she gets a fist-pumping moment when she shoots a rampaging gorilla. Nelson, as well, writes a group of Congo natives with respect, presenting them as reasonable people that would parley with the Claytons. Before they can, though, they are torn to pieces by (what I assume to be) a new ripple in the Tarzan story: half-ape, half-human hybrids. That certainly raises an eyebrow, but it does elevate a reasonably grounded story into the comic book hemisphere, which is welcome.

Like Graig said, Castro’s art is clean and very detailed (people have feet and there are backgrounds!), and reminded me of Cary Nord’s work on Conan. There is, however, that seven page sequence of near silence, punctuated by ape grunts and John’s “No!” I know it’s hard to convey the thoughts and motivation of animals, but this is just too vague. The alpha male of the gorillas kills Kala’s baby (I only know this name because Graig does), then attacks the Clayton house and kills John, but doesn’t stop Kala from taking Tarzan with her. If the alpha was chasing Kala in the first place and killed her baby then, why would he let Kala chase him off later? The passage of time is confusing, and out of context the apes hooting at each other is somewhat ridiculous (more Bendis flashbacks, to that infamous silent issue of Powers at the dawn of time…), so a degree of suspension of disbelief must be accepted. The cover, meanwhile, by Ryan Sook (cover C, apparently) is very striking, depicting Tarzan leaping into battle against baboons. I liked the impressionistic use of silhouettes in the background, and the madness in Tarzan’s eyes is quite vivid, while the style as a whole compliments the interior art well.

Have I been converted By Lord of the Jungle? Nah, but I was entertained. This reads more like it’s aiming for the trade, but at least there are a few ripples of originality. If you’re looking for a familiar tale with a new, but harmless, twist, this is for you.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars