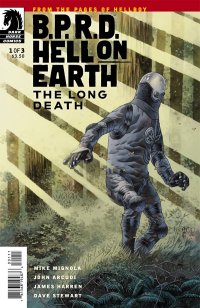

BPRD: Hell on Earth: The Long Death #1 ($3.50)

By Bart Bishop

Hellboy and I go way back. After having grown up with superheroes for years, Hellboy was one of the first “indie” comics that I experimented with. That may sound quaint today, after the character has had two movies (and multiple dtv animated movies) and is practically a household name, but twelve years ago this was a new concept to me. Horror…comics? See, there’s a natural progression for the average comic reader: superheroes leads to Vertigo, which leads to Dark Horse, then anything published by Oni, then Bone, then Strangers in Paradise, then Love & Rockets, and beyond that the sky is the limit. That’s not a concrete order, mind you, especially if Dark Horse’s movie adaptations (Star Wars, Aliens) might be the thing that got you into comics in the first place.

I was skeptical when a solo BPRD series was announced back in 2003. Hellboy had cut ties with the group, leaving the band of monsters and misfits to fend for themelves. That first mini-series, Hollow Earth, was a creative hit that proved the team could stand on their own, and it also kicked off a long-form story with The Plague of Frogs. I have to admit, however, that I’m a fan of the earlier days of Hellboy. There was a pulpier sense of adventure to them, and although there were hints at a greater mythology and destiny for the main character, most of the stories were only loosely connected. BPRD, meanwhile, tends to be heavily predicated upon knowledge of prior stories (it is, after all, 87 issues in) and hard continuity. The tone, as well, has been rather dour at times, as this band of characters feels the weight of the world’s fears and the dread of the known to extreme, creepy degrees.

Furthermore, I love H.P. Lovecraft. For Christmas my girlfriend gifted me The Complete Works of the author, and I read “The Call of Cthulhu” for the first time last month. Very creepy, desolate and foreboding. Mike Mignola has obviously payed homage to Lovecraft freely, but at least with Hellboy his sardonic wit and blunt acceptance of circumstances provided dry humor and low-key slapstick. His comrades in the BPRD, however, need to smile more often. Part of this may stem from Mignola only co-plotting or “producing” the majority of the BPRD series so far. Mostly, however, the weight of history can only be avoided so long in serialized story telling. It’s in the nature of comics, and the original pulps that Mignola idolizes, to navel gaze and pick apart earlier stories to replicate or build upon. With that in mind, I carried this bias with me when opening the pages of Hell on Earth #1.

According to solicitations, “A B.P.R.D. task force is assembled to solve a new series of disappearances in the deadly woods from New World. As the team works together to find the monster responsible, tensions arise over one another’s loyalties!” The focus of this issue is on Johann Kraus, the former medium whose soul is now trapped in a containment suit. Apparently he has recently been exposed to “an ogdru hem creature” and has now been assigned a sleaker, more advanced suit which allows him to dream and may be affecting his behavior. Abe Sapien is in a coma and the rest of the team is away, so Johann is sent to British Columbia to investigate possible monster activity, along with Agent Giarocco who (although I hadn’t encountered her character in the earliest BPRD stories) is one tough cookie.

So the longer I write for CHUD, the more I become aware of the economics of storytelling. I’ve enjoyed John Arcudi’s writing in the past, especially his Dark Horse work in the early ’90’s on the likes of Aliens and The Thing, but he wastes much space in this issue. Several pages are spent depicting Johann’s nightmare of being infected by a monster while only a few panels were necessary to communicate that same information, and the same could be said for the beastly attack that takes up the butt of the book. The reason I mention this is, even with past knowledge of the main characters, I was confused for most of the issue. Hardly any characters are named, and although there’s a nice recap on the first cap it features three characters that don’t make an appearance this issue. Miss Panya, the strange old woman that appears to run the BPRD now, could have used an explanation or two.

So if so much time is spent on horrific action, how does artist James Harren fare? Honestly, his art is ugly. Everyone comes across as bulbous, awkward, and misshapen. This is actually appropriate for a series like this, one that revels in the grotesque, but it hurts the impact of the bizarre characters like Johann when the “normals” are just as doughy and bloated. One particular moment, depicting a baby’s baptism, which is supposed to be beautiful and striking in its realism, is offputting in its incongruousness. Still, Harren does instill shock and awe with his creature designs and slops on the gore. His Abe Sapien, however, although only glimpsed briefly is embarassingly disproportionate and inconsistent with past interpretations. The cover by Duncan Fegredo, however, is a majestic image of Johann in the woods, highlighted by sunrays, like a lost babe which sums up the themes of this issue perfectly. Fegredo manages to combine the alien and the familiar in a much more natural way than Harren.

Not the best start for a new series, but it has a lot of good will. There’s dread and atmosphere a plenty, but it’s all very familiar: Special forces team is sent to deal with supernatural threat and most of the team is wiped out, leaving a mismatched duo to fend for themselves while hashing out personal problems. It’s competently done, but the maudlin mood and murky art isn’t welcoming for new readers, and can’t manage to recreate the old spirit for fans.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

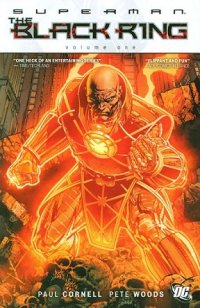

Superman: The Black Ring vol.1 (DC Comics, $14.99)

Superman: The Black Ring vol.1 (DC Comics, $14.99)

by Graig Kent

In the pre-“New 52” DC universe Lex Luthor was a top-tier villain, a bad guy of the highest order that people hated, maybe even loved to hate, but I’m sure there was very little flat-out love for ol’ baldie. Unlike the freakshow of the Joker, the striking armor of Doctor Doom, or the ambiguous morality of Magneto, Lex is just a businessman (and not a “businessman” like Kingpin, but a legitimate capitalist). But does being businessman make him inherently bad or does being stinking rich and superintelligent make him evil? Not for Bruce Wayne or Tony Stark, it doesn’t. No, what made Lex so evil was that, unlike so many of his contemporaries, his evil worked in the shadows, where money, power and intelligence get you whatever you want, and permit you to get away with whatever you want. What made the Lex of not-so-long-ago so unlikeable as a character was his greed, his callousness, his arrogance and most of all his envy. Lex Luthor’s key motivation, the driving factor that makes him Superman’s number one adversary, is his seething resentment of the Man of Steel. It’s such a petty emotion, and the lengths’ Lex goes to in service of envy is pitiable as much as it is dastardly.

Lex was always power-hungry, but when Superman entered his life, he saw a whole other level of power, an inhuman power, one that he wanted but could never obtain. So strong were both his greed and envy, that if he couldn’t have it, he would destroy it. With all that, “pre-New 52 Lex” made for a great villain, but not a very likeable or enjoyable one. It’s interesting then to come to “The Black Ring” (volume 1), the first six chapters of an 11-part arc wherein Lex was, I believe for the first time, the starring character of an ongoing series, and, really for the first time, made into a villain you could root for.

Following the events of “Blackest Night” wherein Lex got his hands on (or finger in) an Orange Lantern ring (avarice) — which was subsequently stripped from him — Lex feels an almost compulsive desire to regain that power. Of course he does. This is the story of his quest.

Writer Paul Cornell admirably resists the common path in making a villain a protagonist, which is to lessen their evil, or sympathize with them, or even turn them into some form of anti-hero. In “The Black Ring” Lex continues to show how ruthless, vile, and malevolent he could be, and does so by pitting him against a series of other super-villains. It’s in pairing him with or putting him up against other villains that he’s shown as being on a completely other level than them (or at least he believes he is). While we may have seen this with Lex before, what Cornell does is inject personality into the man that makes him far more entertaining than ever before. Outside of the Superman films (portrayed by Hackman or Spacey) Lex never had much of a sense of humor, but here, he’s armed with a rather sharp wit one would expect of his intellect. There’s also an exploration of his psyche, his desires and fantasies of which he’s aware, and naturally represses. His arrogance and confidence manifest themselves in Cornell’s story in delightful ways, such as his face-to-face with Neil Gaiman’s Death, a meeting in which Lex actually confesses some vulnerability. While Lex takes himself far too seriously, the story of “The Black Ring” doesn’t, and to Cornell’s credit, it also doesn’t undermine the character. Lex doesn’t become an action hero, per se, but you know he could if he wanted to.

Pete Woods, currently toiling on Legion Lost, is a good choice for a less dour look at Superman’s chief nemesis. Woods has an openness and softness to his lines, and draws characters with great expressiveness, both in their face and their physicality. There’s even a slightly animated, yet weirdly stiff feel to the characters and their movement, the total package reminiscent of the animation style on the FX series Archer. Woods captures Cornell’s take on Lex perfectly, putting a glint in his hazel eyes that speaks volumes of what’s going on in Lex’s mind, and a smug, self-satisfied grin that recalls the mischievous Lex from the pre-Byrne days.

Given what little we’ve seen of Lex Luthor in Grant Morrison’s Action Comics reboot, it’s safe to say that the old Lex has been put to bed. But what an interesting swan song, almost perfectly timed for the reboot, this made.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

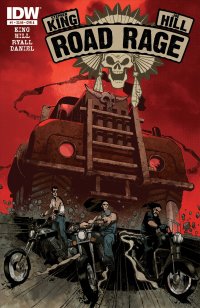

Road Rage #1 of 4 (IDW, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

While movies and comics are both visual media that tell sequential stories, the principal difference is the amount of participation required of the consumer: it is possible (though not necessarily advisable) to make a movie that requires nothing of the viewer more than that they absorb everything coming at them, whereas a comic book has the reader actually tell much of the story to themselves, in between the illustrated panels. While this doesn’t present either medium with an overall inherent “advantage,” there’s something to be said for the total impact that film, through its use of sound and the forced constraint of time, can provide to tales of vehicular mayhem. It’s true that your imagination can bring an awful lot of power to bear on the emotional beats of a story that you read, but for the sheer visceral involvement of a well-executed chase, comics have their work cut out for them to measure up to even something as cheerfully brain-dead as the Fast and Furious films.

I’ve never read Richard Matheson’s “Duel”: like most people, I only became aware of the story in the wake of Steven Spielberg’s masterful TV-movie adaptation, and it seemed unlikely that even Matheson (whose work I generally enjoy) could out-do the nail-biting excitement of the film. But Stephen King is counted among its fans, and a few years back, he and his son, Joe Hill, wrote an homage story called “Throttle” (which I’ve also not read), which appeared in a Matheson tribute anthology called He Is Legend; “Throttle” and “Duel” were later reissued together as Road Rage. IDW’s comic series will adapt both stories in two parts each.

“Duel”, of course, details the frightening encounter that an ordinary driver in a small sedan has with a never-seen, never-explained, but evidently murderous trucker and his 18-wheeler on a lonely stretch of highway; it’s that eerie lack of motivation that keeps the film (and, one presumes, story) lingering in the mind. “Throttle” has a pretty similar premise: a biker gang, about to be sundered by dissent in the wake of bankrolling a meth lab that ended in murderous disaster, encounters a similar truck on a lonely patch of desert highway. King and Hill drop a clue here and there to suggest that their trucker, in fact, is not involved in random existential violence, and I expect that the baked-asphalt bloodbath that ensues over the last few pages of this comic will turn out to have its roots in the familial and criminal backstory that consumes the first ¾ of this issue. But I’ve been wrong before.

Chris Ryall does the actual scripting of the comic, but there’s not that much to it: as the bikers divide into factions, the details are related in conversations and flashback that lay out the fairly simple background, and knowing something of Hill and his dad’s styles, I wouldn’t be surprised if most of it is word for word from the book version. Naturally, it’s artist Nelson Daniel who has the larger share of the responsibility to translate “Throttle” into something that holds the comic reader’s attention, and he acquits himself well, with lots of desert browns and rust. His style runs to the cartoonish, so while you can see, from the cross-hatching and Ben-Day dotted shadows, that the bikers are supposed to be rough-looking, it is a bit distancing that they appear to have clear skin and all their bright white teeth. When the chase ramps up, there is certainly King-level blood spatter all over the place, but it feels disproportionate: I’d have cut the expository stuff in half to give Daniel more time to construct his chase. As it is, it’s more like an explosion of mayhem rather than the buildup that the script seems to need.

If you’ve found yourself caught up in car-chase comics before (The Hire, Supercharger, etc.), you’ll find this well-executed, if a little short on the actual chase stuff. Otherwise, not sure I can give it a huge recommendation. Might make a helluva movie, though.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

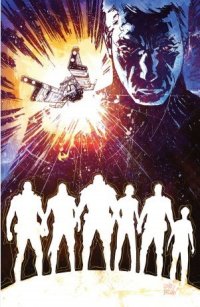

Dark Matter 1-2 ($3.50, Dark Horse

Dark Matter 1-2 ($3.50, Dark Horse

By D.S. Randlett

Mystery seems to have taken over genre storytelling for about the past decade or so. Some would probably attribute this to the popularity of Lost, but I suspect that that show’s style was symptomatic of a larger trend, possibly symptomatic to the point of apotheosis, in most geek friendly shows, movies, and yes, comics. Genre properties are soaked in mystery to the point that character means nothing. Every character has something to hide, and in most cases this makes their actions completely opaque. Story events are waiting for revelations like jokes waiting for punchlines.

It’s easy to see why this style caught on. The big reveal at the end makes you want to catch the next installment. But series, comic book and other wise, that rely on this trick are setting themselves up for failure. Think of it as “Deus Ex Mystery”, where future revelations are thought of more or less as justifications for actions that are taking place in the viewer/reader’s present instead of the natural consequences that arise from the actions and motivations of well-conceived characters. That Dark Matter shares these faults at this point in its run is unsurprising: it is brought to us from a pair of TV writers who have been working in this school for some time now.

The first issue of this space-based science fiction series opens by introducing us to its characters, awakened from their cryo sleep by their ship’s emergency protocols. They remember their skills, they seem to have personalities, but none of them know who they are. They are, in effect, walking mystery bombs. The rest of the first issue is completely action-based: someone rushes to the bridge to save the ship’s life support systems, a security android is awakened, someone remembers that they are a ninja, and the ship is attacked. In theory this is a cool, high-octane opening, but it the lack of any discernible character traits beyond “this person is this kind of ace/badass” helps to leech any tension that this action could possibly have had.

The second issue fares much better as the universe that this series is establishing begins to open itself up some. Fans of Firefly will feel right at home as the amnesiac crew sets down on a down-on-its-luck mining settlement. The people on this world are preparing for the worst: they’ve happened to have settled down on a world that’s conveniently close to a recently discovered asteroid containing vast amounts of something called Quadrium. After a narrow vote, the crew decides to lend a hand to the settlers. Relating what happens next would be spoiling, but it’s enough to redeem the series somewhat.

For all that I’m down on this series, there is much that’s good about it. The world that’s being built is familiar in many ways, but it manages to feel fresh thanks to the art style. Fans of the classic Dark Horse Aliens comics from the nineties will be pleased here, as this universe holds that same coarseness and darkness. This just place feels aggressive. And, for all of my complaining about its slavish devotion to geek mystery tropes, I genuinely do want to see where this story goes.

Hopefully Dark Matter resolves its mysteries sooner rather than later, and in turn finds its characters. There are the seeds for something very solid here, but it remains to be seen whether or not they will bloom.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

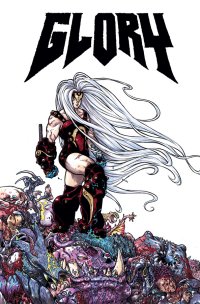

Glory #23 (Image, $2.99)

By Adam Prosser

The comics medium is probably blurrier than any other when it comes to the concept of “authorship”. No one disputes that Bram Stoker is the author of “Dracula”, and despite the many, many adaptations (and perversions?) of the character over the years, the original still stands as the base text. If you’re going to make a new version of Dracula, you’re free to revise, add and subtract from the mythos, but no one’s going to say “It’s not Dracula if he doesn’t look like Christopher Lee!”. With superhero comics, however, later additions to the various mythologies can have the force of canon. Superman’s ability to fly (as opposed to “leaping buildings in a single bound”), his allergy to Kryptonite, his super-pets and Fortress of Solitude, all were added by later writers and artists than Siegel and Schuster, and it’s impossible to imagine Superman without them.

This leads to a lot of complex issues when it comes to sorting out who the creator of a work is, and tends to emphasize the publisher over the writers and artists as the “owner” of a work in the popular imagination, which is where a lot of the current messes derive from. However, even in the case of a character who’s fully owned by his creator, the contributions of others can play a major role. For an example, look at Rob Liefeld’s creation Glory, relaunching this week (surprisingly, maintaining the old numbering, which at this point seems almost as unusual as starting a series again from #1 used to be) from Joe Keatinge and Ross Campbell.

As originally conceived by Liefeld, Glory was an obvious Wonder Woman analogue, the daughter of the goddess Demeter and a demon called Silverfall, who had descended to Earth to fight in World War II as part of a team of retro-Golden Age superheroes Liefeld used to pad out the history of his “Youngblood” Universe. Keatinge and Campbell are following not only in the footsteps of Liefeld, but also Alan Moore, who reworked the character as a supporting player in his excellent run on Supreme and had planned a spinoff title which unfortunately fizzled due to the big comics crash of the mid-90s. Moore added the idea that Glory had decided to inhabit the body of a mentally unbalanced waitress named Gloria West to experience life on Earth, and reworked it as a “mystical romance” comic. (Moore also injected a lot of ideas about magic and myth that he ended up transposing, perhaps more successfully, to Promethea.)

Keatinge stays more or less within these guidelines, but he also seems to be changing details of the mythos as he sees fit. He does keep a surprising amount of Moore’s ideas, though the mythology is different. Actually what really stands out is Campbell’s rather radical new character designs. Glory herself is certainly a memorable image, a hypermuscled albino amazon who manages to look both graceful and strong, and Campbells’ knack for expressive faces and distinctive characters manifests itself throughout the book. The new character of Riley, a journalist who works as a viewpoint character, introducing us to Glory’s history through her attempts to locate her present whereabouts, is a great example, looking rather as if she stepped out of a Derek Kirk Kim comic. This is a terrific example of how a fresh art style can really invigorate superheroics. Combine the fact that Glory, despite her history, is a relative blank slate—Keatinge’s script pretty much hits all the high points of her “continuity”, such as it is, in a couple of pages, with room left over for his own additions—and you’ve got a terrific example of a highly fresh and accessible book.

I’ve often felt that what superheroes really need is to sprout some new branches away from the trunk of Marvel and DC, a place where there’s no status quo to shake up and room to create something from scratch that might actually appeal to new readers. Glory’s not quite a new character, but she’s certainly unshackled by the heavy weight of continuity and, perhaps more crucially, her authors show a delightful willingness to think outside the box that is the superhero paradigm. Like its titular character, Glory manages to be old and new at the same time, and keep the best aspects of both.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars